Abstract

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) has long been the standard locoregional therapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, while transarterial radioembolization (TARE) using yttrium-90 microspheres has emerged as a promising alternative driven by advances in dosimetry and improved outcomes. TARE offers high complete response rates, durable local control, and minimal post-embolization syndrome, particularly in patients with localized or large tumors and preserved hepatic function. However, its broader use is limited by radiation-related toxicity, technical challenges, and socioeconomic factors, including high cost and limited repeatability. In contrast, TACE remains widely applicable, repeatable, and cost-effective, achieving excellent tumor control through refined superselective techniques, especially in Korea. Rather than competing modalities, TARE and TACE should be integrated within a tailored treatment strategy, with the choice determined by tumor characteristics, hepatic reserve, and institutional expertise.

-

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Therapeutic radioembolization; Therapeutic chemoembolization

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a hypervascular malignancy that arises predominantly in cirrhotic livers, and its arterial vascularity makes transarterial therapy a key component of disease management [

1-

5]. Since the 1980s, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) has been established as the cornerstone of locoregional therapy for unresectable HCC, with its efficacy in improving tumor response and survival confirmed by pivotal randomized controlled trials, large-scale Japanese cohort studies, and subsequent meta-analyses [

6-

10]. Building on this robust evidence, TACE remains the most widely recommended treatment for patients with large or multifocal HCC and is also extensively employed both as an initial therapy and as a salvage option for post-treatment recurrence [

3-

5].

In recent years, transarterial radioembolization (TARE) using yttrium-90 (Y-90) microspheres has shown a rapid increase in clinical use, driven by advances in personalized dosimetry, improved treatment planning, and accumulating evidence of favorable tumor control and survival outcomes [

11,

12]. In Korea, the expansion of National Health Insurance coverage for TARE since December 2020 has accelerated its clinical adoption, especially in patients with larger tumor burdens or in those considered unsuitable for surgical resection or other locoregional therapy [

13].

This review is based on two recent publications in the Korean Journal of Radiology: the 2023 Korean Liver Cancer Association expert consensus on TACE and the 2025 review on optimizing Y-90 TARE dosimetry for HCC [

13,

14]. Building on the core principles discussed in these works, this article provides a comparative overview of TACE and TARE, focusing on their therapeutic mechanisms, advantages, limitations, and optimal indications within Korean clinical practice. This context inevitably leads to a central clinical question: Can TARE realistically replace TACE in the management of HCC?

TARE Compared with TACE: Treatment Mechanisms

TACE achieves tumor necrosis through ischemic injury and cytotoxic effects induced by transarterial infusion of chemoembolic materials [

14,

15]. To enhance tumor response and minimize injury to non-tumorous parenchyma, superselective catheterization is crucial. In conventional TACE, chemotherapeutic agents are mixed with lipiodol, an iodized poppy seed oil that has been used for more than a century as an oil-based contrast agent in radiology (e.g., lymphangiography and myelography), to form a radiopaque emulsion that allows real-time fluoroscopic visualization of the chemoembolic material distribution [

14].

TARE, also known as selective internal radiation therapy, delivers Y-90 labeled microspheres into the hepatic artery [

13]. These particles lodge in the tumor microvasculature and emit β-radiation, producing tumoricidal effects without causing complete arterial occlusion. In the aspect of treatment mechanism, TARE more closely resembles external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) than TACE. However, EBRT delivers homogeneous, calibrated doses to a defined target, whereas TARE distributes radiation heterogeneously according to tumor vascularity and microsphere deposition, even with advances in predictive dosimetry modeling. Two types of Y-90 microspheres are commercially available in Korea: glass microspheres and resin microspheres. In glass microspheres, Y-90 is embedded within a glass matrix, resulting in higher density and a high specific activity of approximately 4,000 Bq per particle, producing minimal embolic effect. In contrast, resin microspheres consist of Y-90 coated onto a resin core, with lower specific gravity and specific activity of around 50 Bq per particle, leading to a relatively greater embolic effect and a more uniform distribution within the tumor vascular bed.

The dose–response relationship in Y-90 TARE is a critical determinant of therapeutic efficacy. Because glass and resin microspheres differ in their physical and radiologic characteristics, they exhibit distinct dose–response thresholds. Glass microspheres generally require a higher tumor-absorbed dose to achieve comparable treatment outcomes, whereas resin microspheres, with their lower specific activity and larger particle number, can exert a stronger radiobiologic effect even at lower absorbed doses [

16]. For HCC, the tumoricidal absorbed dose is generally considered to be approximately in the range of >205–260 Gy for glass microspheres and >100–157 Gy for resin microspheres [

13]. Increasing evidence supports a strong positive correlation between tumor-absorbed dose and tumor response, emphasizing the importance of personalized dosimetry to achieve adequate tumor irradiation while minimizing radiation injury to non-tumorous liver parenchyma [

11,

17].

TARE Compared with TACE: Pros

Recent advances in dosimetry optimization have markedly improved the therapeutic outcomes of TARE. Radiation segmentectomy and radiation lobectomy have expanded the role of TARE from a palliative treatment to a potentially curative modality. In early or localized HCC, radiation segmentectomy can achieve complete necrosis by delivering ablative radiation doses confined to one or two hepatic segments (

Fig. 1). In the LEGACY study, which included patients with solitary HCCs (median diameter, 2.7 cm; range, 1.0 to 8.1 cm), radiation segmentectomy achieved a 2-year complete response (CR) rate of 84% [

12]. In the RASER trial, a single-center prospective study conducted in patients with solitary HCCs ≤ 3 cm, the initial objective response rate was 100 % [

18]. This outcome was superior to that reported in a Korean retrospective study (2-year CR rates in 1–10 cm HCCs: 66.2% with conventional TACE and 30.5% with drug-eluting bead TACE [DEB-TACE]) and a Japanese randomized controlled trial (3-month CR rates in 1–5 cm HCCs: 75.2% with conventional TACE and 27.6% with DEB-TACE) [

19,

20]. Several studies have further demonstrated that radiation segmentectomy can achieve local tumor control rates comparable to those of surgical resection or local ablation, when appropriate dosimetry is achieved [

21]. Even for multifocal or bulky tumors, Korean investigators have expanded this principle beyond segmentectomy into a broader concept of radiation “major hepatectomy,” applying ablative doses to larger anatomical territories when disease remains confined and hepatic reserve is adequate (

Fig. 2). A Korean study reported a median time to progression of 17.1 months in patients with tumors averaging 11.4 cm in size treated at mean absorbed doses of 418.8 Gy [

22]. Radiation lobectomy can also be used when resection is technically feasible but unsafe because the future liver remnant (FLR) is insufficient [

23]. By intentionally delivering sufficient radiation dose to non-tumorous parenchyma in the target lobe, contralateral hypertrophy can be induced while simultaneously suppressing tumor progression in the treated lobe [

24]. Taken together, these results indicate that territory-based TARE with high radiation dose can serve as a reasonable alternative in patients who are technically resectable but medically inoperable, or in those initially considered for resection who later become unsuitable because of comorbidities or limited hepatic reserve [

25].

Because the therapeutic effect of TARE is driven by radiation-induced cytotoxicity rather than ischemic injury, the incidence of post-embolization syndrome, which presents with abdominal pain, fever, and transient elevation of liver enzymes, is lower than that observed after TACE [

26]. As a result, patients experience faster recovery, shorter hospitalization, and better overall tolerance. In Western countries, TARE is frequently performed on an outpatient basis, whereas in Korea it is typically carried out during a short-term hospital stay, reflecting differences in healthcare systems, reimbursement policies, and institutional practice patterns.

The minimal ischemic insult associated with TARE also translates into improved quality of life after treatment [

27]. Patients generally experience fewer postprocedural symptoms and require less analgesic or supportive care. Furthermore, because radiation segmentectomy achieves high CR rates, TARE provides durable tumor control that often reduces the need for repeated transarterial sessions. This decreased frequency of retreatment lowers the cumulative treatment burden and enhances long-term patient convenience and satisfaction. Collectively, these features make TARE a well-tolerated and patient-friendly therapeutic option, particularly for individuals who may not tolerate the ischemic and systemic stress associated with TACE.

TARE Compared with TACE: Cons

TARE carries several radiation-related and technical limitations that restrict its broader clinical application. Radiation pneumonitis is one of the significant complications of TARE, resulting from inadvertent shunting of Y-90 microspheres into the pulmonary circulation [

28]. To minimize this risk, Western guidelines typically recommend limiting the lung dose to <30 Gy per TARE session and <50 Gy cumulatively over a lifetime. However, Korean cohort data indicate that clinically significant radiation pneumonitis has occurred even at lung doses below these Western thresholds, which may be related to smaller lung mass and higher effective radiation exposure per unit dose [

29]. Therefore, a more conservative lung dose limit is advisable in Korean practice, particularly for patients with preexisting pulmonary disease or advanced liver cirrhosis [

13]. For example, modified thresholds are generally applied in my clinical practice; <25 Gy for males and <20 Gy for females when using glass microspheres, and <15 Gy for resin microspheres, assuming a lung mass of approximately 1 kg. Because of this cumulative radiation constraint, patients who have undergone prior TARE often become ineligible for repeat treatment, even when intrahepatic recurrence later develops. This inherent limitation contrasts with TACE, which can be safely repeated multiple times as long as hepatic function is preserved, thereby allowing more flexible long-term disease control.

Another significant complication is radioembolization-induced liver disease (REILD), caused by radiation injury to non-tumorous liver parenchyma. REILD typically manifests as jaundice, ascites, and hepatic failure in the absence of tumor progression, and histologically corresponds to sinusoidal obstruction and veno-occlusive injury [

30]. Because the absorbed radiation dose to normal liver correlates directly with hepatotoxicity, adequate hepatic reserve and a sufficient FLR are critical prerequisites for safe treatment. Patients with Child-Pugh class B or C liver function or marginal FLR are at markedly increased risk of hepatic decompensation. In practice, the safety threshold for TARE should approximate that of hepatic resection, with an FLR of at least 30% of total liver volume while preserving two contiguous Couinaud segments considered essential [

5,

13]. Given the higher prevalence of cirrhosis and smaller baseline liver volumes in Korean patients, a more conservative approach is often warranted. In my clinical practice, the irradiated liver volume should not exceed approximately 50% of the total normal parenchyma, and treatment should be limited to Child-Pugh class A patients with clearly demarcated arterial territories, such as localized HCCs. These precautions are crucial to minimize the risk of REILD and to preserve post-treatment hepatic function, especially when repeat or sequential therapy is anticipated, as most HCC patients ultimately require additional treatments during their lifetime. Although TARE often achieves higher CR rates, this does not necessarily translate into longer survival. There have been no large-scale randomized controlled trials comparing TARE with TACE. According to three small comparative studies and subsequent meta-analyses published before 2020, there were no significant differences in overall survival or safety outcomes between the two treatments [

31].

From a procedural standpoint, TARE also presents inherent technical challenges. Unlike conventional TACE, in which chemoembolic materials are radiopaque and their distribution can be continuously observed under fluoroscopy, Y-90 microspheres are invisible during infusion, making real-time monitoring impossible [

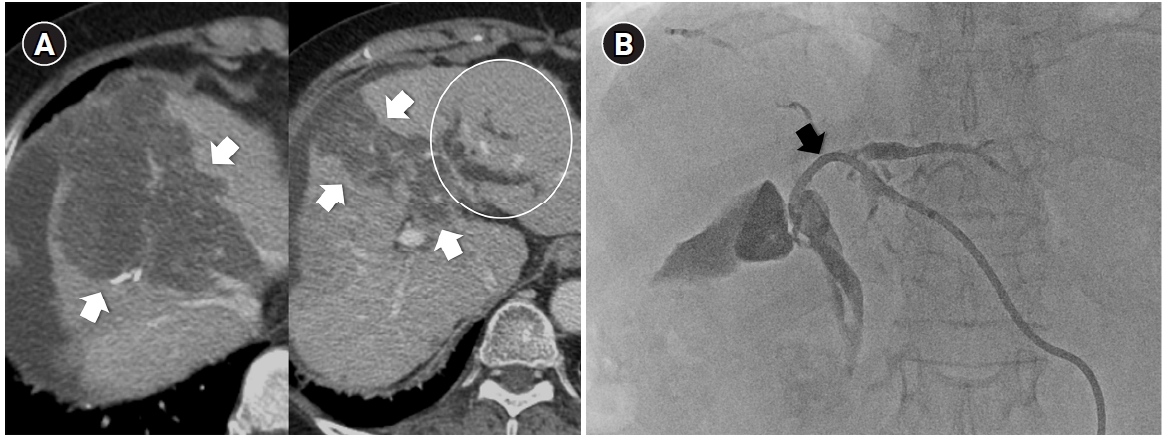

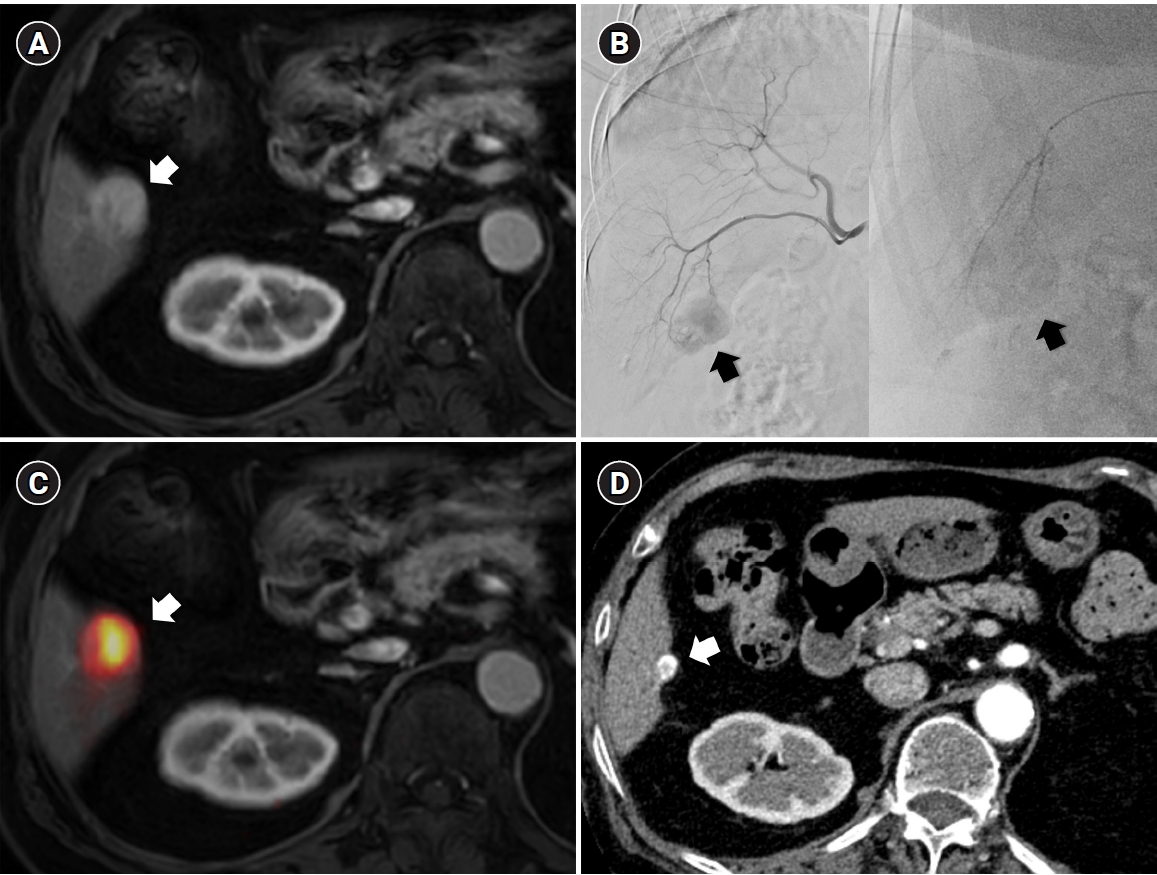

13]. Although a technetium-99m–labeled macroaggregated albumin scan is performed pre-procedurally to simulate microsphere distribution, actual flow dynamics during treatment may differ, often resulting in a wider-than-anticipated infusion territory and unintended radiation exposure to non-tumorous liver parenchyma. This unpredictability can contribute to hepatotoxicity or even REILD, particularly when the functional liver reserve is marginal. In addition, for central or hilar lesions, the inability to monitor microsphere flow raises another critical concern. When excessive embolic effect occurs in fine caudate or peribiliary arteries, flow stasis cannot be detected in real time, leading to prolonged high-dose radiation exposure to the peribiliary plexus and subsequent central bile duct injury [

32] (

Fig. 3). Therefore, achieving a truly selective and controlled infusion is technically more challenging with TARE than with TACE, where the infusion of chemoembolic materials can be directly visualized and adjusted during the procedure. These limitations underscore a fundamental difference between the two modalities: whereas TACE allows dynamic control and immediate correction of reflux or over-embolization, TARE relies entirely on pre-procedural planning and hemodynamic prediction, making the actual treatment field less predictable and inherently less selective.

TARE is also resource-intensive and logistically demanding. It requires close coordination among interventional radiology, nuclear medicine, and radiation safety teams. The Y-90 microspheres must be imported and used within a limited calibration window, complicating scheduling and procedural timing [

13]. Comprehensive pre-treatment work-up, including mapping angiography, prophylactic embolization, and MAA scanning is mandatory, followed by post-treatment Y-90 positron emission tomography for dose verification. Furthermore, the procedure demands substantial expertise and experience. Mastery of radiation physics, dosimetry modeling, and complex hepatic flow dynamics requires a long learning curve, and the actual procedure often takes longer than conventional TACE due to detailed dose planning and safety verification. In the Korean healthcare environment, the cost of a single TARE session remains several times higher than that of TACE. As TARE use expands, its impact on the National Health Insurance expenditures is expected to increase although there are some clinical scenarios the need for fewer repeat treatments may partially offset the overall cost. These technical, educational, and socioeconomic challenges collectively limit the accessibility and scalability of TARE despite its proven therapeutic potential.

Comparative Indications and Clinical Applications

Given the advantages and limitations discussed above, it is evident that TARE cannot fully replace TACE in the treatment of HCC. Instead, these two modalities should be considered complementary tools that can be selectively applied according to tumor characteristics, liver function, and patient condition (

Table 1). The therapeutic goal should not be to choose one modality over the other, but rather to combine them in a way that maximizes efficacy while minimizing hepatic injury.

TARE is particularly advantageous in early or localized HCC where curative-intent therapy is feasible, but surgery or ablation is not possible. Radiation segmentectomy can achieve high CR rates and durable local control, making it a reasonable alternative for patients who are technically resectable but medically inoperable. Because it induces minimal ischemic injury and has a low incidence of post-embolization syndrome, TARE is also suitable for elderly patients, those with comorbidities, or individuals with poor performance status who may not tolerate TACE. In addition, for patients with large tumor burden, TARE can be used as an initial debulking strategy to reduce tumor volume before subsequent TACE or systemic treatments.

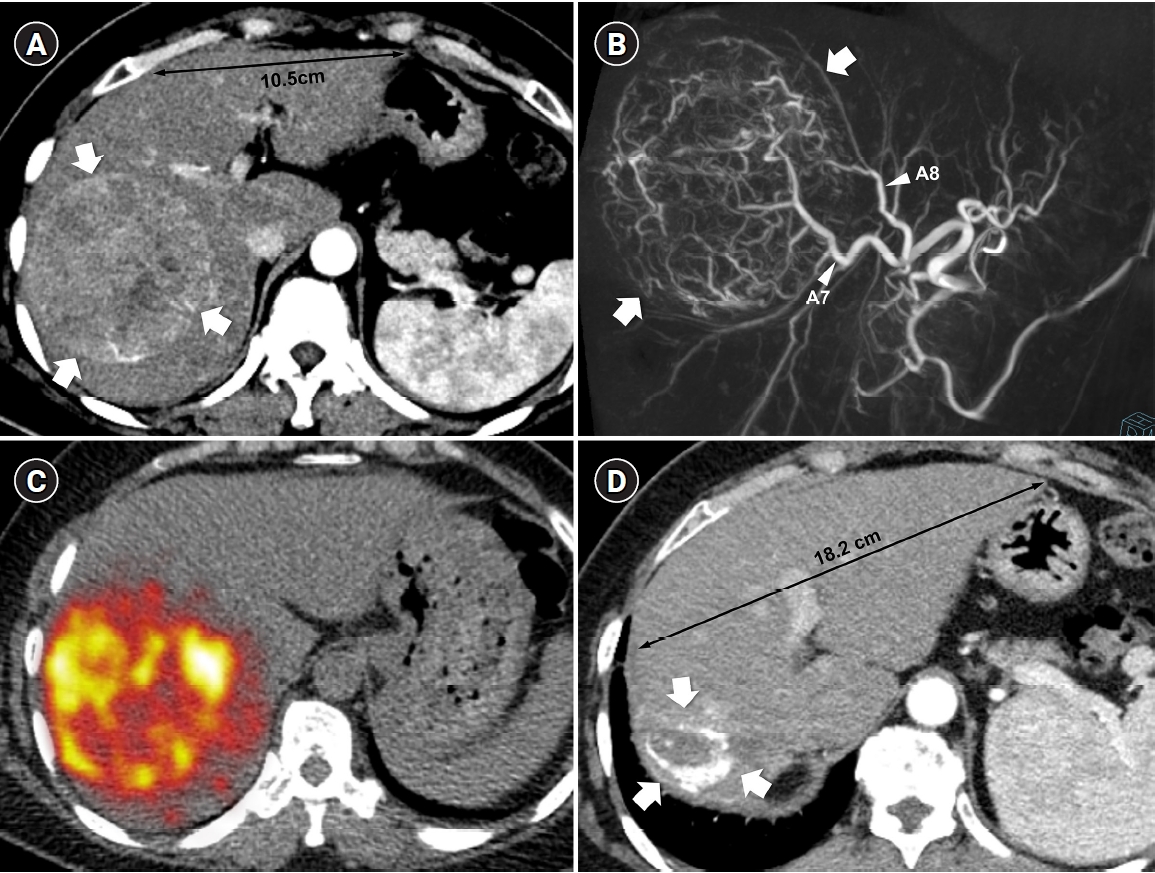

Conversely, TACE remains the backbone of transarterial therapy due to its broad applicability, repeatability, and controllability. It can be safely performed in a wide range of clinical settings as long as hepatic function is preserved. The National Cancer Center–Korean Liver Cancer Association guidelines continue to recommend TACE as the best or alternative treatment option across most stages of HCCs, underscoring its versatility and reliability [

5]. Moreover, the ability to visualize lipiodol-based emulsions under fluoroscopy allows for real-time monitoring and precise control, enabling superselective embolization that maximizes tumor necrosis while sparing functional parenchyma [

14] (

Fig. 4). There is a report that superselective TACE yielded survival outcomes similar with early HCC for patients beyond Milan but within up-to-seven criteria [

33]. Korean interventional radiologists, in particular, have achieved remarkable tumor control through refined superselective techniques, even in anatomically complex or high-risk cases where other modalities may not be feasible. The technical sophistication developed in East Asia, especially in Korea and Japan, has produced outcomes that often exceed those reported in Western studies [

6]. Using meticulous microcatheter techniques, embolization can be performed safely even in patients with marginal hepatic reserve or tumors near critical structures, minimizing non-target injury while maintaining high tumor response rates. In Korea, TACE is not only technically advanced but also widely accessible and cost-effective, supported by a national insurance system that enables most tertiary and regional hospitals to perform the procedure. In my opinion, perhaps half in jest, no other country can offer such highly selective TACE at such an affordable cost, which reflects both the skill of Korean interventional radiologists and the efficiency of the healthcare system.

Conclusion

TARE and TACE should not be regarded as competing procedures but as complementary components of a personalized treatment strategy for HCC. TARE offers durable local control and better tolerability, making it suitable for localized or large tumors in patients with preserved hepatic function or limited procedural tolerance. In contrast, TACE provides procedural precision, broad applicability, and repeatability, maintaining its role as the backbone of transarterial therapy across most clinical stages. In clinical practice, sequential or combined use may achieve a better balance between efficacy and safety (

Figs. 5,

6) [

34]. Ultimately, the choice between TARE and TACE should be individualized according to tumor characteristics, hepatic reserve, and institutional expertise, and that optimal HCC management depends on integration rather than substitution.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

The author discloses the use of ChatGPT-4o (www.openai.com) for English language editing and proofreading of this manuscript.

Author contributions

The author conducted all aspects of the study.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

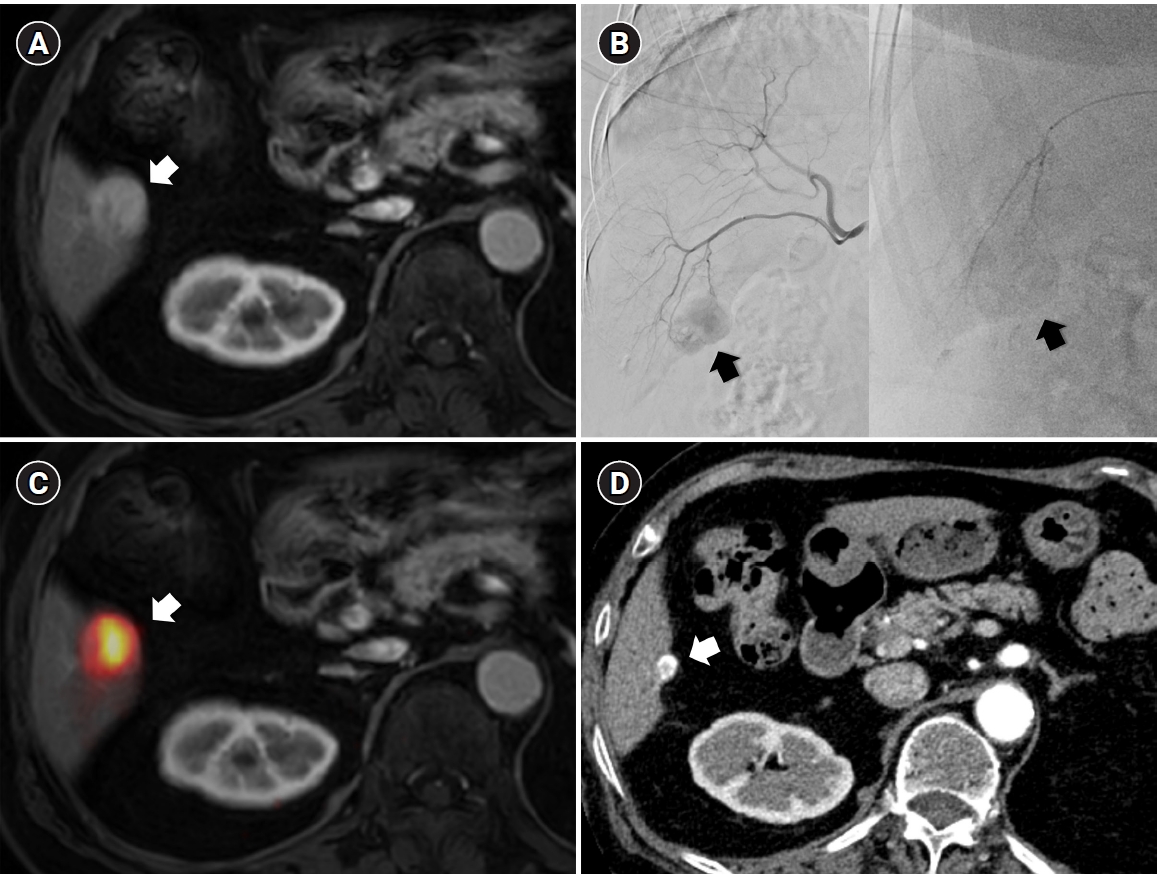

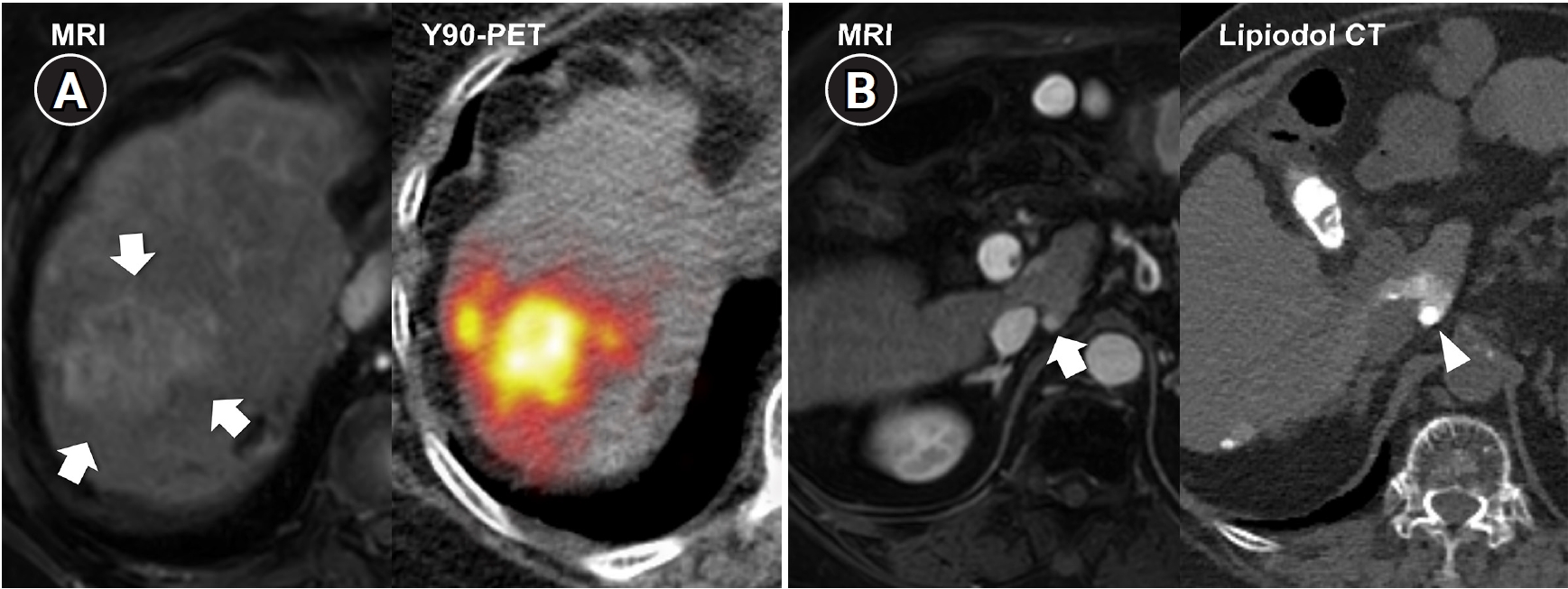

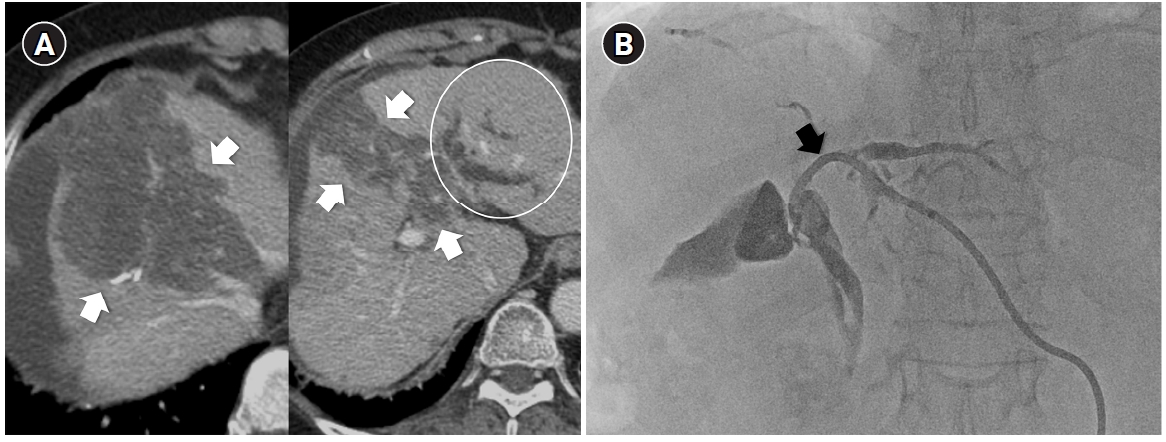

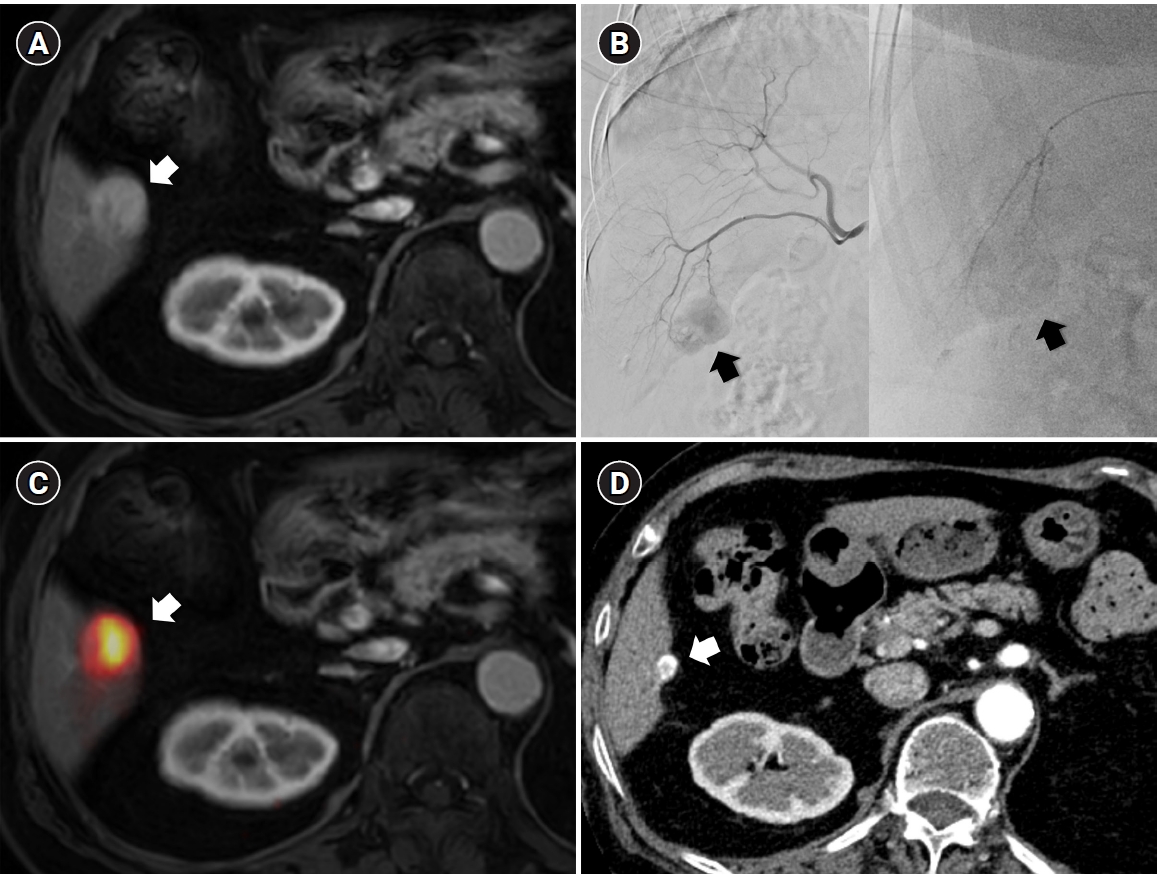

Fig. 1.Radiation subsegmentectomy in an 86-year-old man with a single nodular hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) Liver magnetic resonance imaging shows a 2.2-cm hypervascular tumor (arrow) with exophytic growth in segment 6. (B) Hepatic arteriography shows a hypervascular tumor (arrows), and the microcatheter was advanced into a subsegmental branch of A6 (right side image). A total activity of 0.35 GBq of glass microspheres was infused. (C) Post-treatment Y-90 positron emission tomography shows intense uptake at the tumor (arrow), confirming a perfused liver dose of 508.7 Gy and a tumor dose of 1,794.7 Gy. Voxel-based dosimetry showed a D95 of 625 Gy and a V200 of 100%. (D95: the minimum dose delivered to 95% of the target volume, V200: the percentage of target volume receiving ≥200 Gy). (D) Twenty-month follow-up computed tomography shows complete response with dystrophic calcification (arrow).

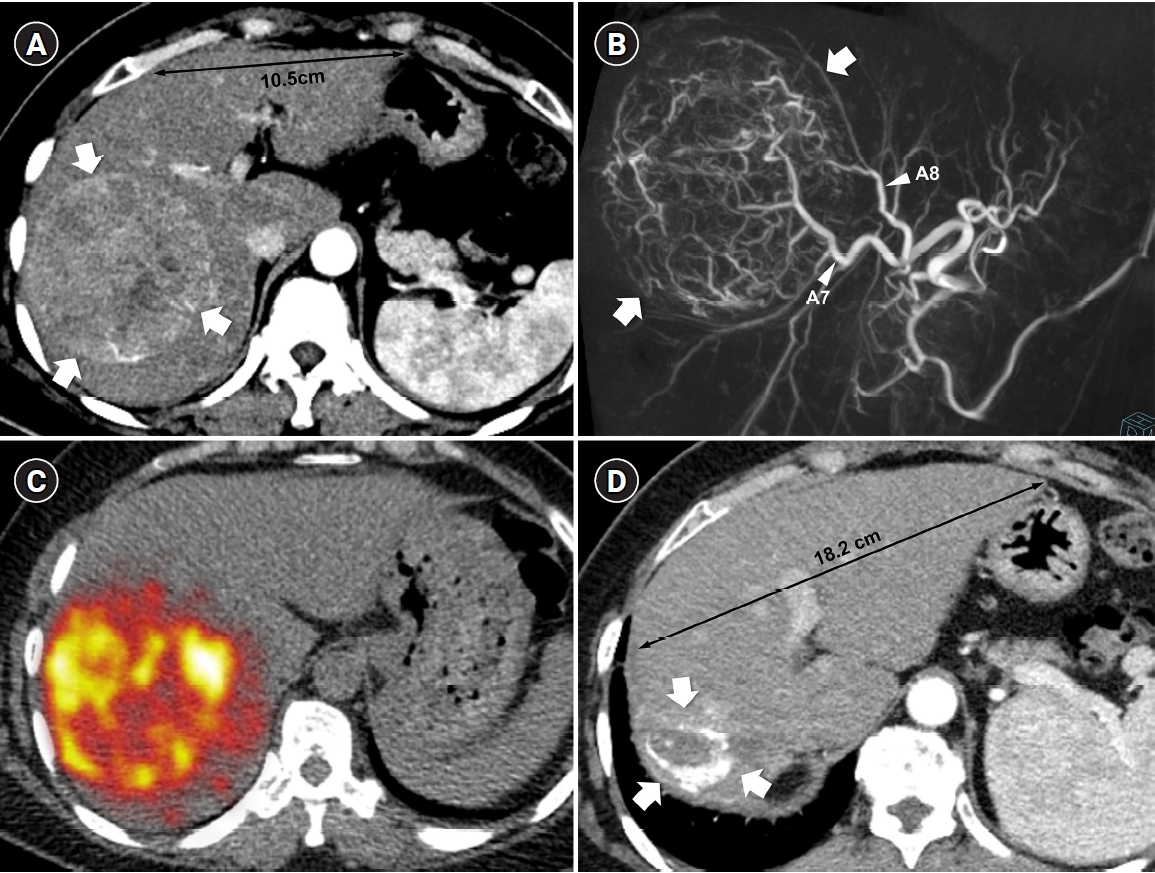

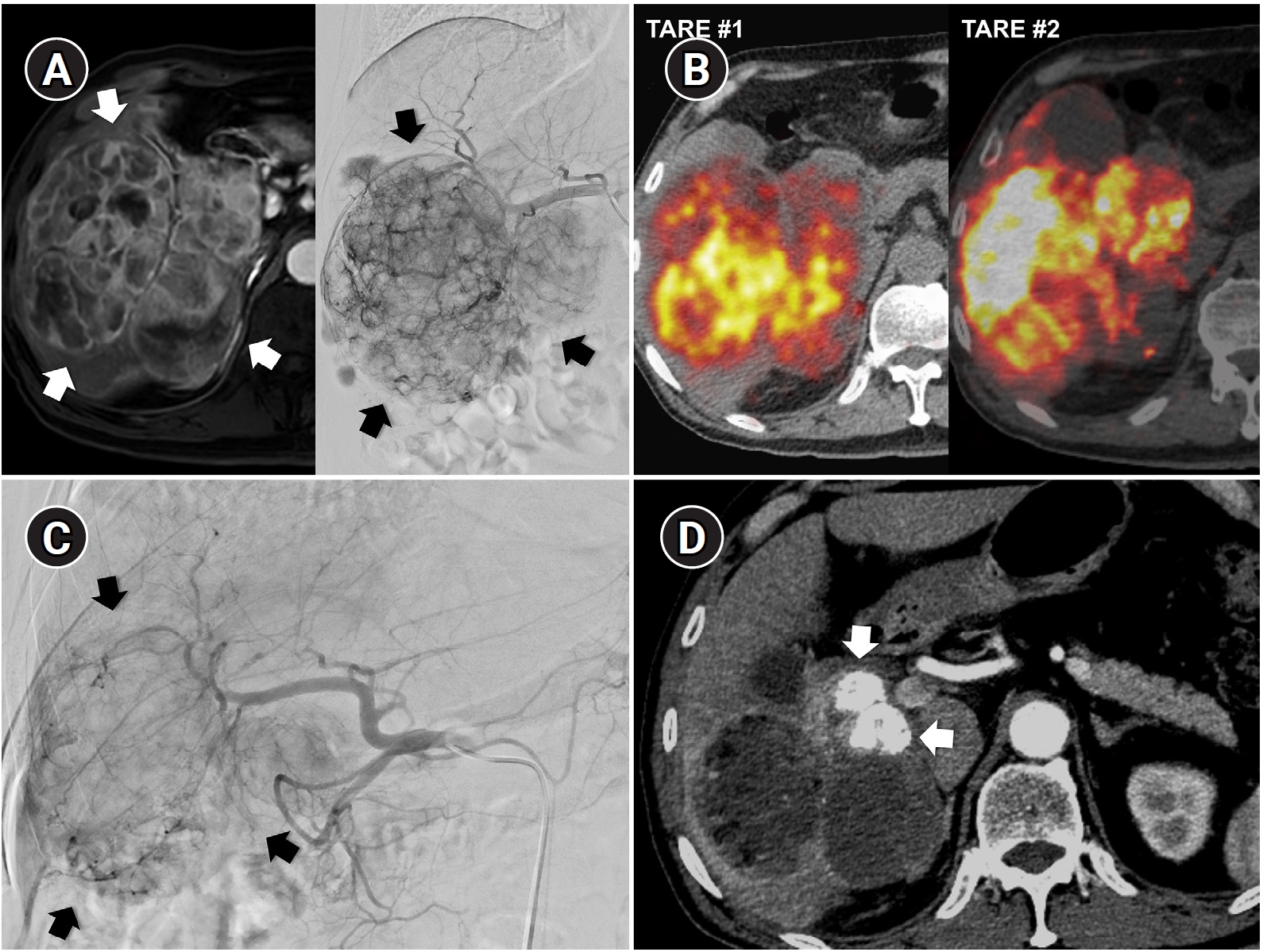

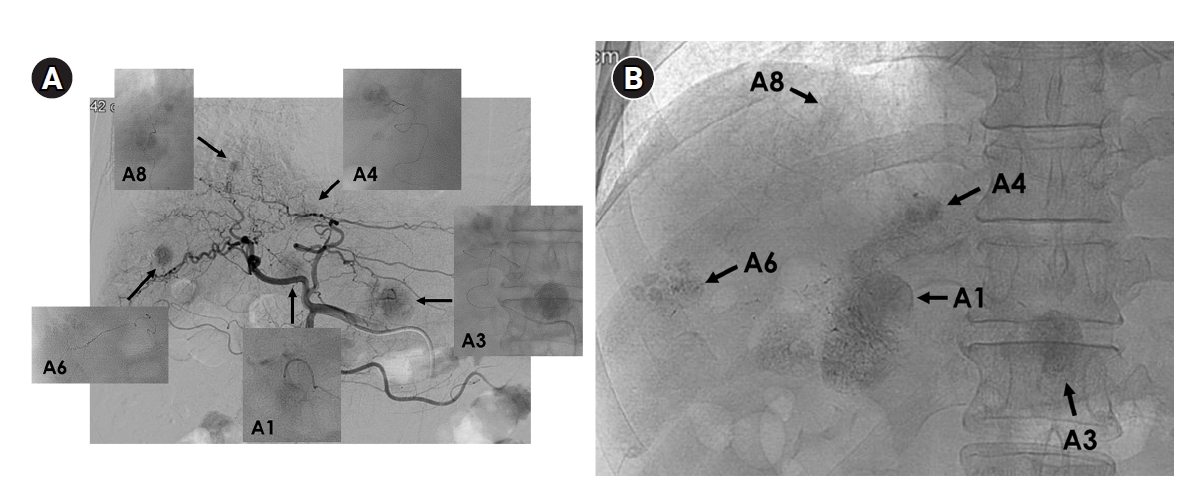

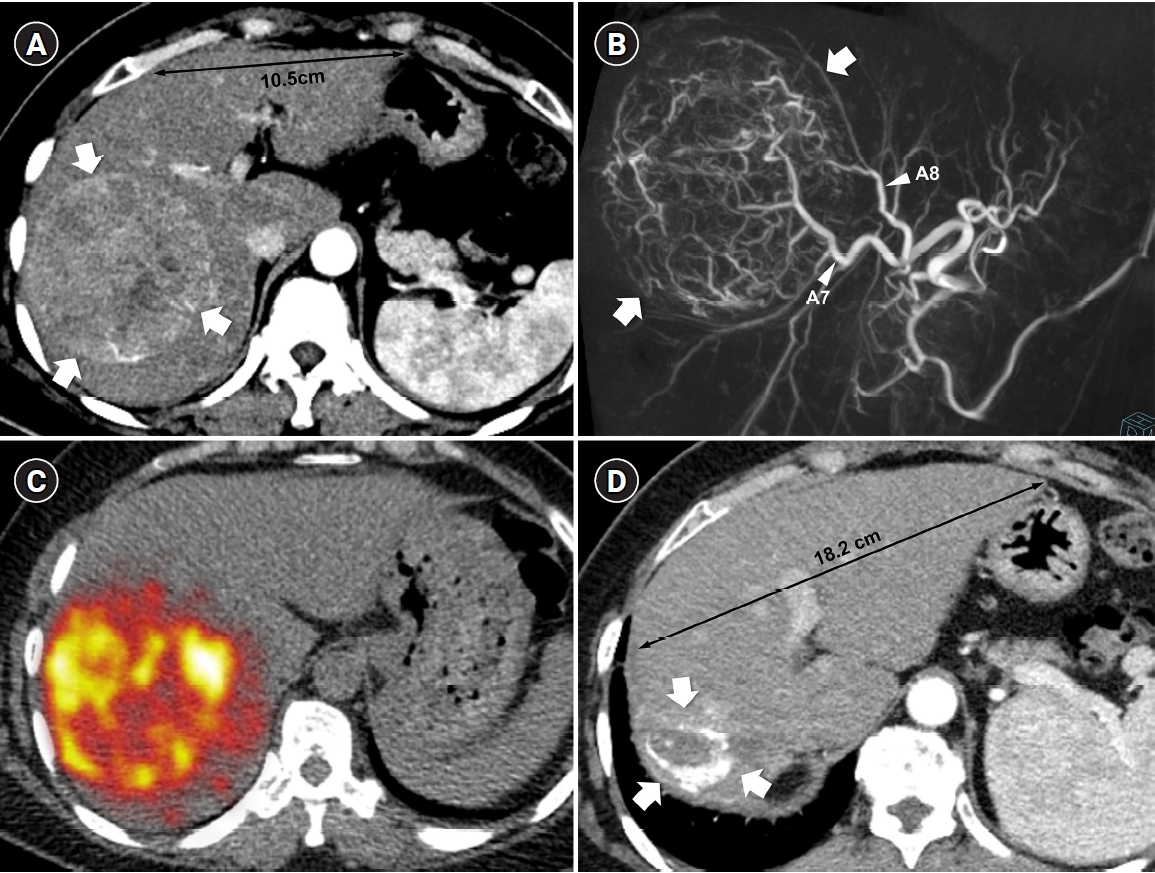

Fig. 2.Radiation major hepatectomy in a 60-year-old woman with hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) shows a 9.0-cm hypervascular tumor (arrows) with two satellite nodules (not shown) in segments 7 and 8. (B) Cone-beam CT hepatic arteriography shows tumor staining (arrows) supplied by A7 and A8 (arrowheads). A total of 9.11 GBq of glass microspheres was infused via A7 and A8. (C) Post-treatment Y-90 positron emission tomography shows intense uptake throughout the tumor, consistent with complete microsphere coverage, with a perfused liver dose of 355.3 Gy and a tumor dose of 609.9 Gy. (D) Fifty-month follow-up CT shows complete response with dystrophic calcification (arrows), atrophy of segments 7 and 8, and compensatory hypertrophy of the left hepatic lobe (double arrowheads).

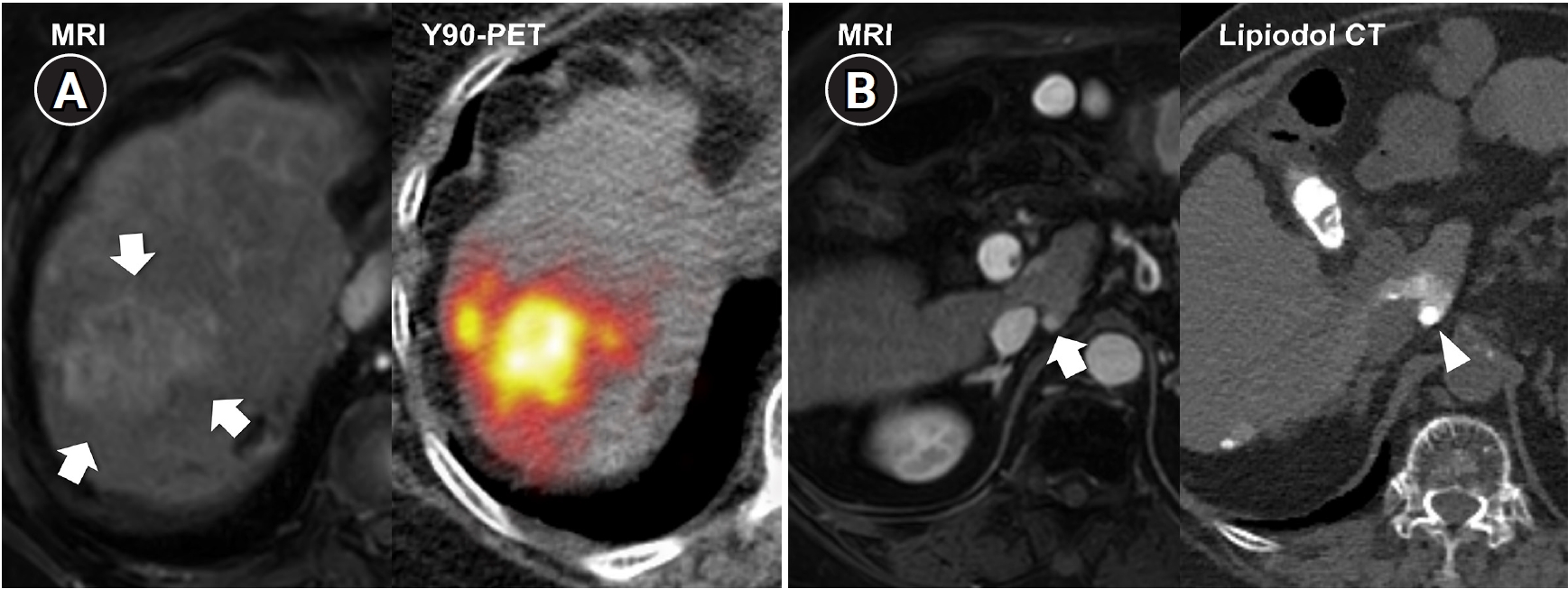

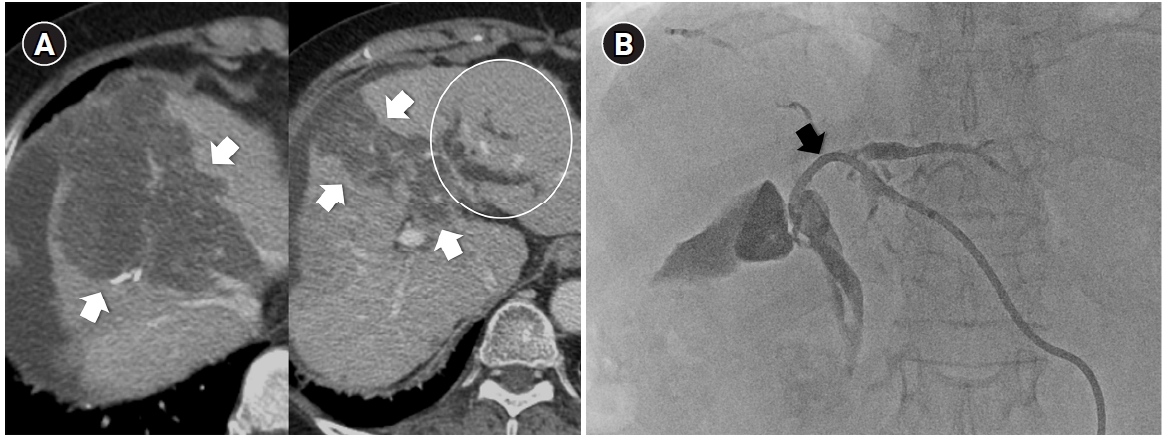

Fig. 3.Central bile duct injury after transarterial radioembolization in an 80-year-old woman with ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) Computed tomography obtained 5 months after selective infusion of Y-90 microspheres via A1, A4, and A8 shows extensive radiation necrosis (arrows) in segments 4 and 8, with dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (circle) in the left lateral segments. (B) Because of progressive jaundice and pruritus, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was performed, and cholangiography showed segmental occlusion of the left main bile duct (arrow), suggesting radiation-induced ductal injury.

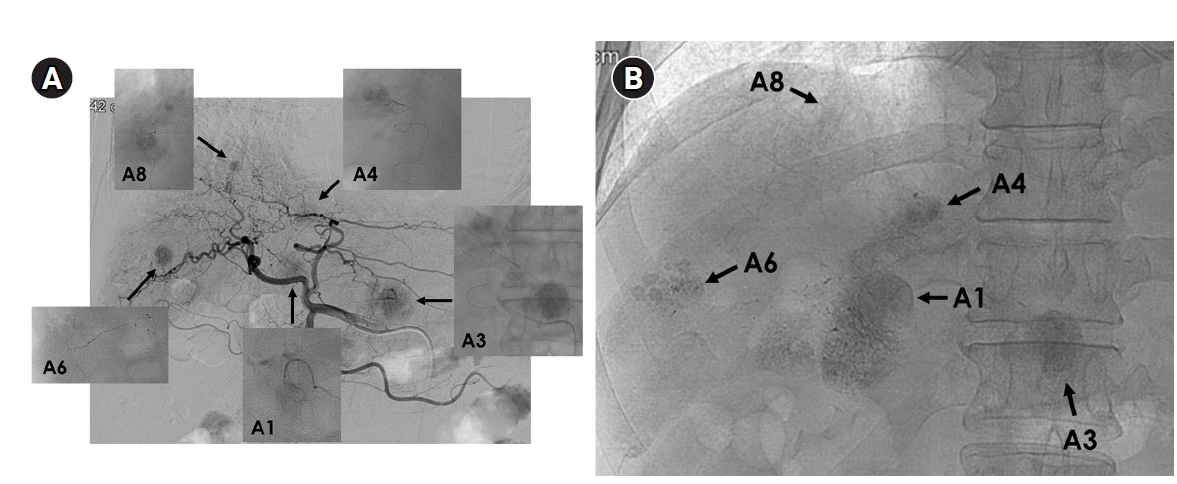

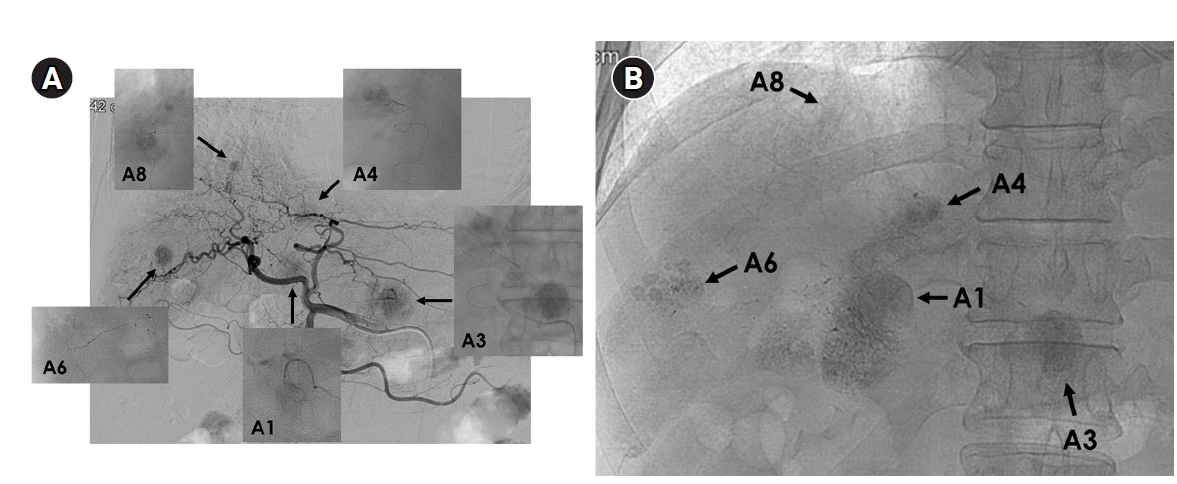

Fig. 4.Superselective transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) for five nodular tumors in a 60-year-old man. (A) Common hepatic arteriography shows five nodular tumors. Superselective TACE was performed through tumor-feeding arteries including A1, A3, A4, A6, and A8. (B) Post-TACE fluoroscopy shows dense lipiodol uptake within the tumors without significant parenchymal deposition.

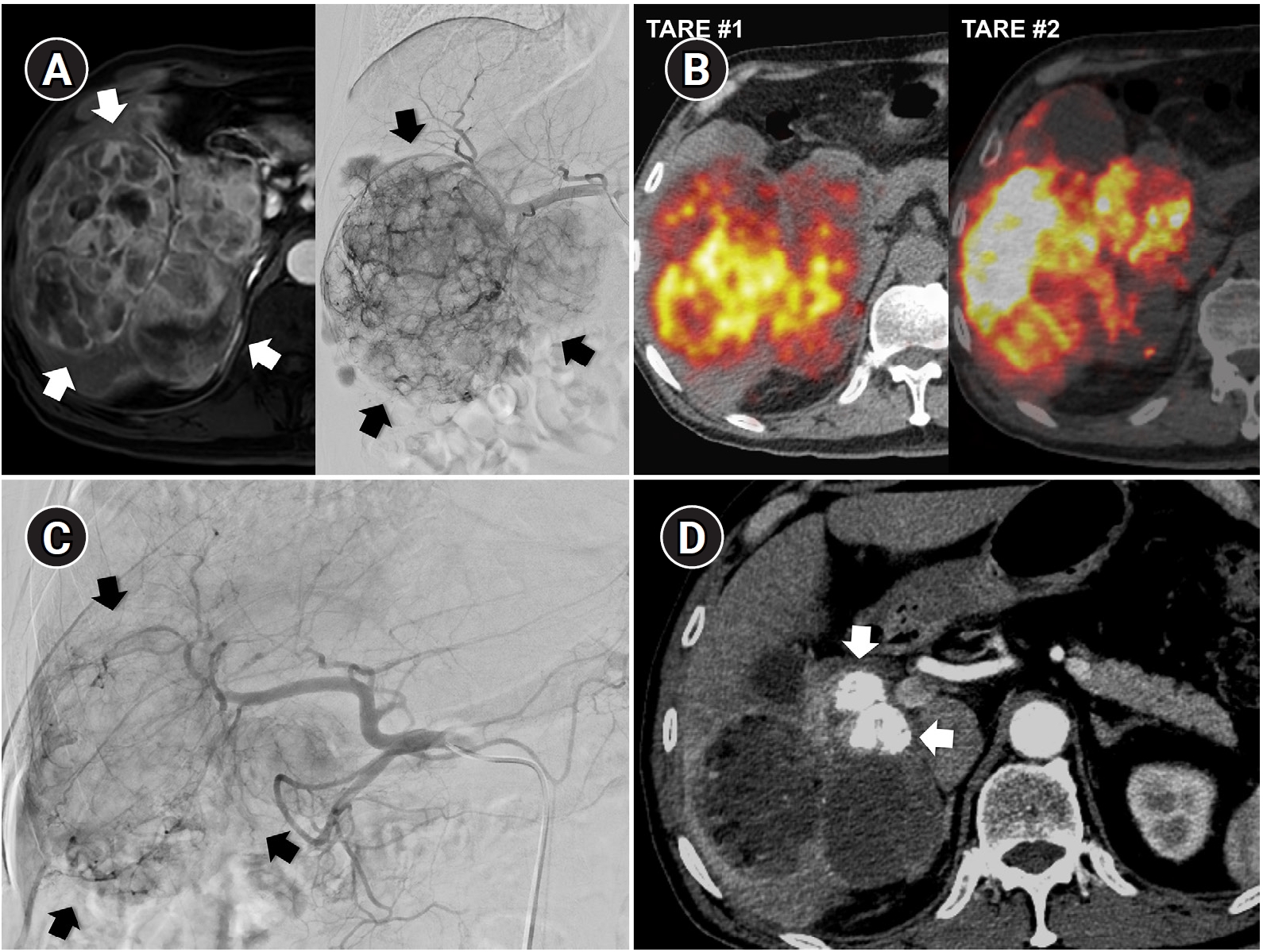

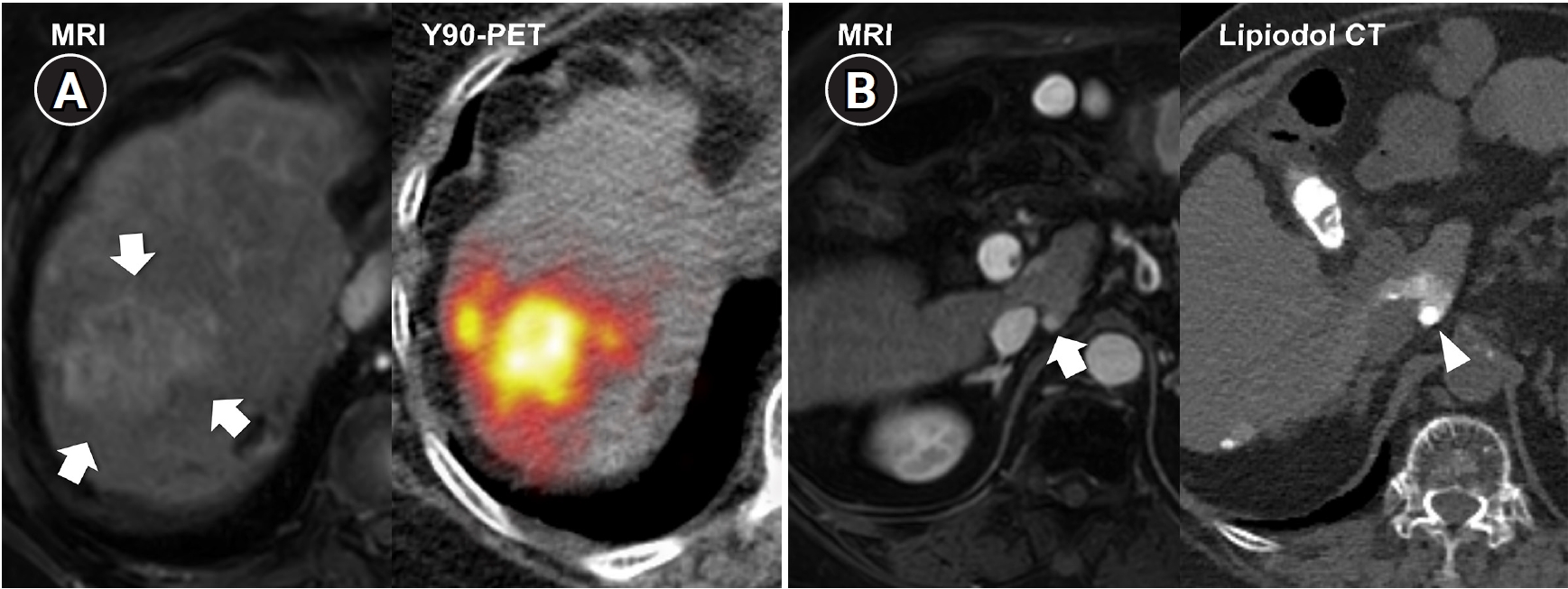

Fig. 5.Combined transarterial radioembolization (TARE) and superselective transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) performed during planning angiography in a 78-year-old man with multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (two lesions). (A) Liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows a recurrent 4.7-cm lobulating tumor (arrows) at the previous TACE-treated site. To change the treatment mechanism from chemoembolization to radiation-based therapy, radiation segmentectomy was performed with 1.18 GBq of glass microspheres via A7 and A8. (B) Liver MRI also shows a new 0.6-cm nodule (arrow) in the Spiegel lobe. During planning angiography, superselective TACE was performed for this lesion to avoid excessive radiation exposure to the central liver. Lipiodol computed tomography (CT), obtained immediately after chemoembolization, shows dense lipiodol uptake (arrowhead) confined to the tumor. Y-90 PET, yttrium-90 positron emission tomography.

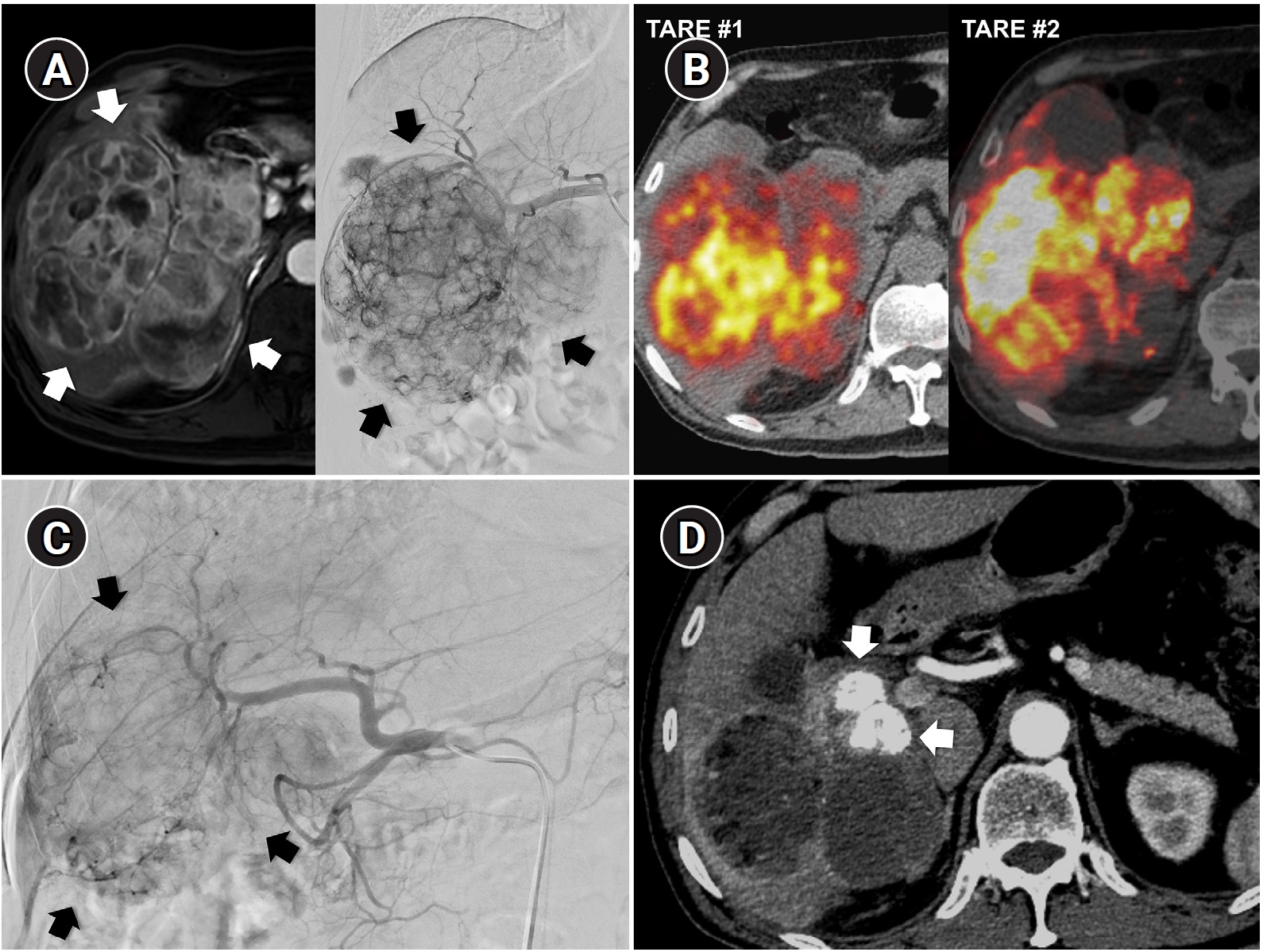

Fig. 6.Sequential transarterial radioembolization (TARE) followed by transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in a 77-year-old man with large hepatocellular carcinoma. (A) Magnetic resonance imaging and angiography show a 12.5-cm conglomerated mass (arrows) with multiple satellite nodules in segments 5, 6, and 7. (B) Sequential TARE was planned because a single session could not achieve sufficient tumor dose owing to lung dose limitation. In TARE #1 (5.0 GBq resin microspheres), perfused liver dose was 178 Gy and lung dose was 9.6 Gy. In TARE #2 (5.5 GBq resin microspheres), perfused liver dose was 255 Gy and lung dose was 12.2 Gy. Post-treatment Y-90 positron emission tomography/computed tomography demonstrates heterogeneous intratumoral Y-90 activity in the tumors. (C) Angiography 5 months after TARE #2 shows decreased tumor staining (arrows) in the right lobe. TACE was performed through multiple subsegmental branches supplying residual tumor. (D) After two additional TACE sessions (not shown), the computed tomography obtained 2 years after the initial TARE showed decreased tumor size, near-complete disappearance of arterial enhancement, and partial lipiodol uptake (arrows) in the tumor.

Table 1.Comparison of TARE and cTACE in key clinical domains

Table 1.

|

Domain |

TARE |

cTACE |

|

Treatment mechanism |

Radiation-induced cytotoxicity |

Ischemia and intra-arterial chemotherapy |

|

Local tumor control/CR rates |

Higher and more durable in localized tumors (radiation segmentectomy) |

Slightly lower, operator-dependent |

|

Overall survival |

Comparable |

Comparable |

|

Contralateral hypertrophy induction |

Effective (radiation lobectomy) |

Less effective |

|

Superselective delivery |

Limited (invisible microsphere delivery) |

Excellent (real-time Lipiodol visualization under fluoroscopy) |

|

Repeatability |

Limited by cumulative lung dose and hepatic reserve |

Repeatable as long as liver function preserved |

|

Post-embolization syndrome |

Less frequent |

More frequent |

|

Hospital stay |

Shorter |

Longer |

|

Cost/reimbursement burden |

Higher |

Lower |

|

Medical resource requirement |

Higher (multidisciplinary, complex scheduling) |

Lower |

References

- 1. Bargellini I, Florio F, Golfieri R, Grosso M, Lauretti DL, Cioni R. Trends in utilization of transarterial treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a survey by the Italian Society of Interventional Radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:438-444; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-013-0656-5.

- 2. Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE study. Liver Int. 2015;35:2155-2166; https://doi.org/10.1111/liv.12818.

- 3. Han JW, Sohn W, Choi GH, Jang JW, Seo GH, Kim BH, et al. Evolving trends in treatment patterns for hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea from 2008 to 2022: a nationwide population-based study. J Liver Cancer. 2024;24:274-285; https://doi.org/10.17998/jlc.2024.08.13.

- 4. Hong YM, Yoon KT, Cho M, Kang DH, Kim HW, Choi CW, et al. Trends and patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma treatment in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:403-409; https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.3.403.

- 5. Korean Liver Cancer Association (KLCA) and National Cancer Center (NCC) Korea. 2022 KLCA-NCC Korea practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2022;23:1126-1240; https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2022.0822.

- 6. Lencioni R, de Baere T, Soulen MC, Rilling WS, Geschwind JF. Lipiodol transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of efficacy and safety data. Hepatology. 2016;64:106-116; https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28453.

- 7. Llovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734-1739; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08649-X.

- 8. Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164-1171; https://doi.org/10.1053/jhep.2002.33156.

- 9. Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, Omata M, Okita K, Ichida T, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:461-469; https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.021.

- 10. Takayasu K, Arii S, Kudo M, Ichida T, Matsui O, Izumi N, et al. Superselective transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Validation of treatment algorithm proposed by Japanese guidelines. J Hepatol. 2012;56:886-892; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.021.

- 11. Garin E, Tselikas L, Guiu B, Chalaye J, Edeline J, de Baere T, et al. Personalised versus standard dosimetry approach of selective internal radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (DOSISPHERE-01): a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:17-29; https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30290-9.

- 12. Salem R, Johnson GE, Kim E, Riaz A, Bishay V, Boucher E, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for the treatment of solitary, unresectable HCC: the LEGACY study. Hepatology. 2021;74:2342-2352; https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31819.

- 13. Lee IJ, Kim HC. Optimizing Yttrium-90 radioembolization dosimetry for hepatocellular carcinoma: a Korean perspective. Korean J Radiol. 2025;26:688-703; https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2025.0308.

- 14. Cho Y, Choi JW, Kwon H, Kim KY, Lee BC, Chu HH, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: 2023 expert consensus-based practical recommendations of the Korean Liver Cancer Association. Korean J Radiol. 2023;24:606-625; https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2023.0385.

- 15. Young S, Craig P, Golzarian J. Current trends in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with transarterial embolization: a cross-sectional survey of techniques. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:3287-3295; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-018-5782-7.

- 16. Walrand S, Hesse M, Chiesa C, Lhommel R, Jamar F. The low hepatic toxicity per Gray of 90Y glass microspheres is linked to their transport in the arterial tree favoring a nonuniform trapping as observed in posttherapy PET imaging. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:135-140; https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.113.126839.

- 17. Lam M, Garin E, Maccauro M, Kappadath SC, Sze DY, Turkmen C, et al. A global evaluation of advanced dosimetry in transarterial radioembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma with Yttrium-90: the TARGET study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:3340-3352; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-022-05774-0.

- 18. Kim E, Sher A, Abboud G, Schwartz M, Facciuto M, Tabrizian P, et al. Radiation segmentectomy for curative intent of unresectable very early to early stage hepatocellular carcinoma (RASER): a single-centre, single-arm study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:843-850; https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00091-7.

- 19. Lee IJ, Lee JH, Lee YB, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Yin YH, et al. Effectiveness of drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization versus conventional transarterial chemoembolization for small hepatocellular carcinoma in Child-Pugh class A patients. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919866072; https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835919866072.

- 20. Ikeda M, Arai Y, Inaba Y, Tanaka T, Sugawara S, Kodama Y, et al. Conventional or drug-eluting beads? Randomized controlled study of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: JIVROSG-1302. Liver Cancer. 2022;11:440-450; https://doi.org/10.1159/000525500.

- 21. Salem R, Padia SA, Toskich BB, Callahan JD, Fowers KD, Geller BS, et al. Radiation segmentectomy for early hepatocellular carcinoma is curative. J Hepatol. 2025;82:1125-1132; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2025.01.005.

- 22. Choi JW, Suh M, Paeng JC, Kim JH, Kim HC. Radiation major hepatectomy using ablative dose yttrium-90 radioembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma 5 cm or larger. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2024;35:203-212; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2023.10.011.

- 23. Vouche M, Lewandowski RJ, Atassi R, Memon K, Gates VL, Ryu RK, et al. Radiation lobectomy: time-dependent analysis of future liver remnant volume in unresectable liver cancer as a bridge to resection. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1029-1036; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.015.

- 24. Bekki Y, Marti J, Toshima T, Lewis S, Kamath A, Argiriadi P, et al. A comparative study of portal vein embolization versus radiation lobectomy with Yttrium-90 micropheres in preparation for liver resection for initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 2021;169:1044-1051; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2020.12.012.

- 25. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2025;82:315-374; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2024.08.028.

- 26. Benguerfi S, Estrade F, Lescure C, Rolland Y, Palard X, Le Sourd S, et al. Selective internal radiation therapy in older patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:417-421; https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0000000000002255.

- 27. Das A, Gabr A, O'Brian DP, Riaz A, Desai K, Thornburg B, et al. Contemporary systematic review of health-related quality of life outcomes in locoregional therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:1924-1933; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2019.07.020.

- 28. Sangro B, Martinez-Urbistondo D, Bester L, Bilbao JI, Coldwell DM, Flamen P, et al. Prevention and treatment of complications of selective internal radiation therapy: expert guidance and systematic review. Hepatology. 2017;66:969-982; https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29207.

- 29. Kim HC, Kim GM. Radiation pneumonitis following Yttrium-90 radioembolization: a Korean multicenter study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:977160; https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2023.977160.

- 30. Sangro B, Gil-Alzugaray B, Rodriguez J, Sola I, Martinez-Cuesta A, Viudez A, et al. Liver disease induced by radioembolization of liver tumors: description and possible risk factors. Cancer. 2008;112:1538-1546; https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23339.

- 31. Casadei Gardini A, Tamburini E, Inarrairaegui M, Frassineti GL, Sangro B. Radioembolization versus chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:7315-7321; https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S175715.

- 32. Kim HC, Joo I, Lee M, Chung JW. Benign biliary stricture after yttrium-90 radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:2014-2021; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2020.07.024.

- 33. Arizumi T, Ueshima K, Iwanishi M, Minami T, Chishina H, Kono M, et al. Validation of a modified substaging system (Kinki criteria) for patients with intermediate-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2015;89 Suppl 2:47-52; https://doi.org/10.1159/000440631.

- 34. Kwon JH, Kim GM, Han K, Won JY, Kim MD, Lee DY, et al. Safety and efficacy of transarterial radioembolization combined with chemoembolization for bilobar hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-center retrospective study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:459-465; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-017-1826-7.