Abstract

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) are rare congenital vascular anomalies characterized by a direct connection between pulmonary arteries and veins, resulting in right-to-left shunting, arterial hypoxemia, and an increased risk of paradoxical embolic events. Endovascular embolization has become the standard of care for the treatment of PAVMs, significantly reducing the risk of neurologic and hemorrhagic complications. However, optimal patient selection, choice of embolic materials, procedural strategies, and post-treatment surveillance remain areas of active evolution. This review provides an interventional radiologist–focused overview of contemporary practice in PAVM management. Key topics include the clinical relevance of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, current indications for treatment in adult and pediatric populations, and periprocedural strategies to minimize complications such as air embolism and catheter-related thrombosis. Advances in embolic materials, including detachable coils, venous sac embolization techniques, and vascular plugs, are discussed with an emphasis on their relative efficacy and impact on recanalization and reperfusion rates. Procedure-related complications and their management are reviewed, highlighting both common self-limiting events and rare but serious adverse outcomes. Finally, current approaches to post-embolization surveillance are summarized, with a focus on the role of computed tomography, metal artifact reduction techniques, and emerging dynamic imaging modalities such as time-resolved magnetic resonance angiography for detecting treatment failure. By integrating recent evidence and practical procedural considerations, this review aims to support interventional radiologists in optimizing the safety, durability, and long-term outcomes of PAVM embolization.

-

Keywords: Pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas; Embolization; Magnetic resonance angiography; Surveillance; Endovascular

Introduction

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (PAVMs) are rare congenital vascular anomalies of the lung characterized by direct communication between a pulmonary artery and vein without an intervening capillary bed [

1]. This leads to the direct passage of arterial blood into the venous system, resulting in arterial hypoxemia and an increased risk of paradoxical embolism. Such paradoxical embolism can lead to complications like brain infarction, brain abscess, transient ischemic attack, or even myocardial infarction [

2-

5]. Additionally, PAVMs carry a risk of rupture and hemorrhage, which can lead to significant complications for the patient [

6]. As an interventional radiologist specializing in the embolization of PAVMs, it is essential to understand the clinical implications of the associated hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), as well as the advantages and limitations of current embolic materials. Furthermore, a comprehensive evaluation of the various embolization techniques and the appropriate post-procedural follow-up is crucial. This review article aims to provide a thorough synthesis of these aspects, thereby enhancing clinical practice and patient outcomes.

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

HHT is an autosomal dominant disease with an estimated prevalence of 1 in 5,000 [

7]. It is characterized by clinically significant vascular lesions involving the skin and mucosa (nasal and gastrointestinal), as well as the brain, lungs, and liver. It is underdiagnosed, and a long diagnostic delay is common [

8]. A diagnosis of HHT allows appropriate screening and preventive treatment to be undertaken in a patient and their affected family members. The most common symptom of HHT, epistaxis, has an age-related expression, as does the appearance of the typical telangiectasia (

Fig. 1). The diagnosis of HHT is well described in Curaçao criteria (

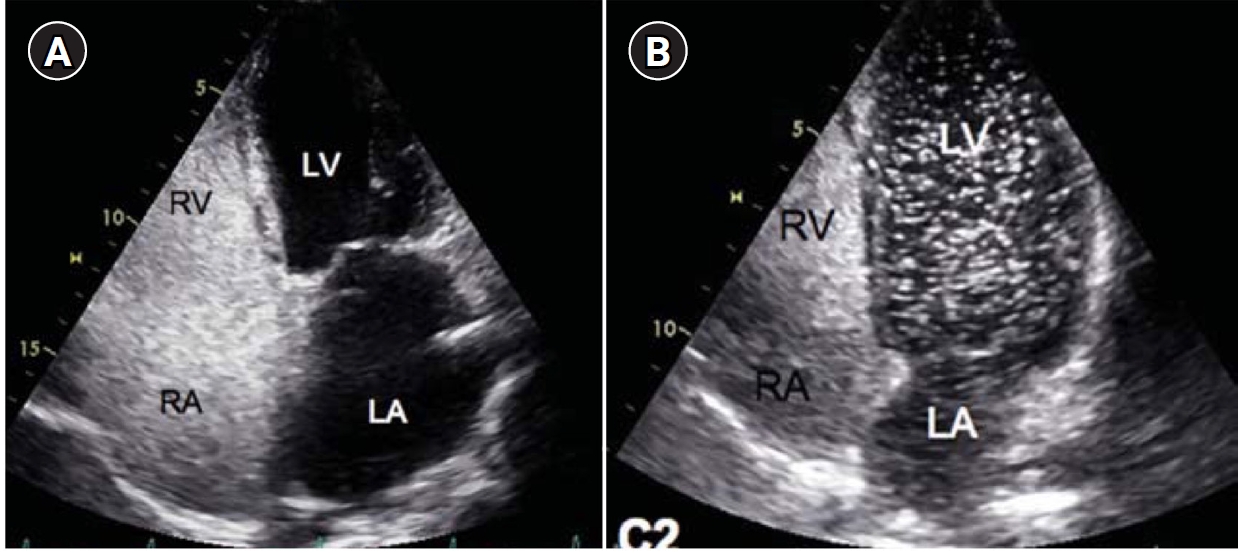

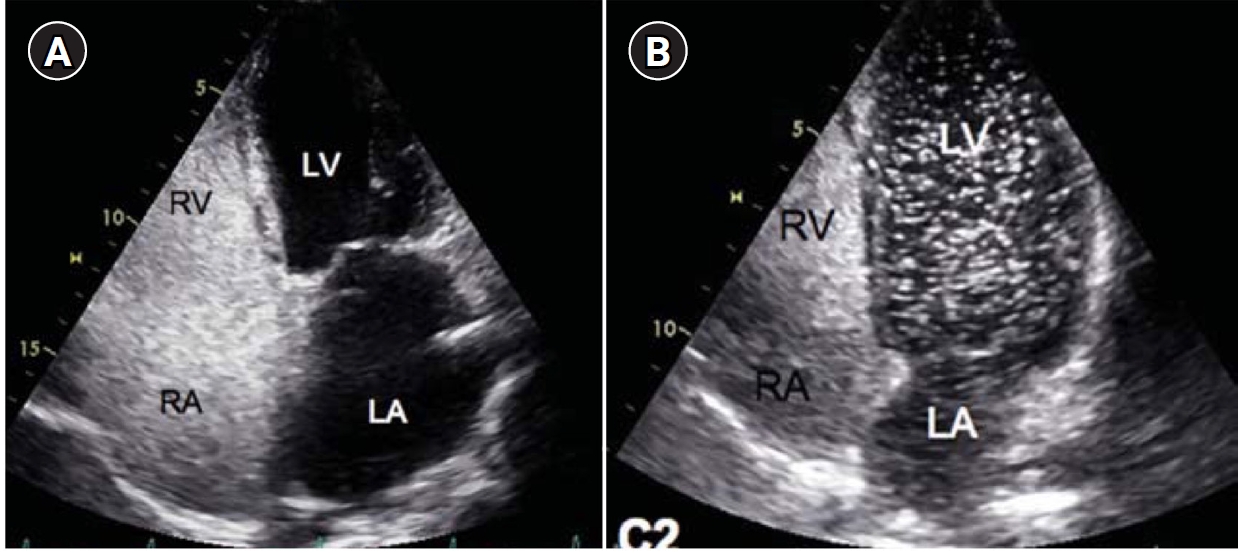

Table 1). In patients with symptoms or signs of a PAVM by history and/or physical examination, contrast-enhanced or agitated saline bubble echocardiography remains the best initial screening tool because of its high sensitivity and negative predictive value approaching 100% (

Fig. 1) [

9]. According to the expert panel, if HHT is confirmed or suspected, a workup for PAVMs is necessary, and for this workup, contrast-enhanced echocardiography is recommended [

10].

Treatment Indications

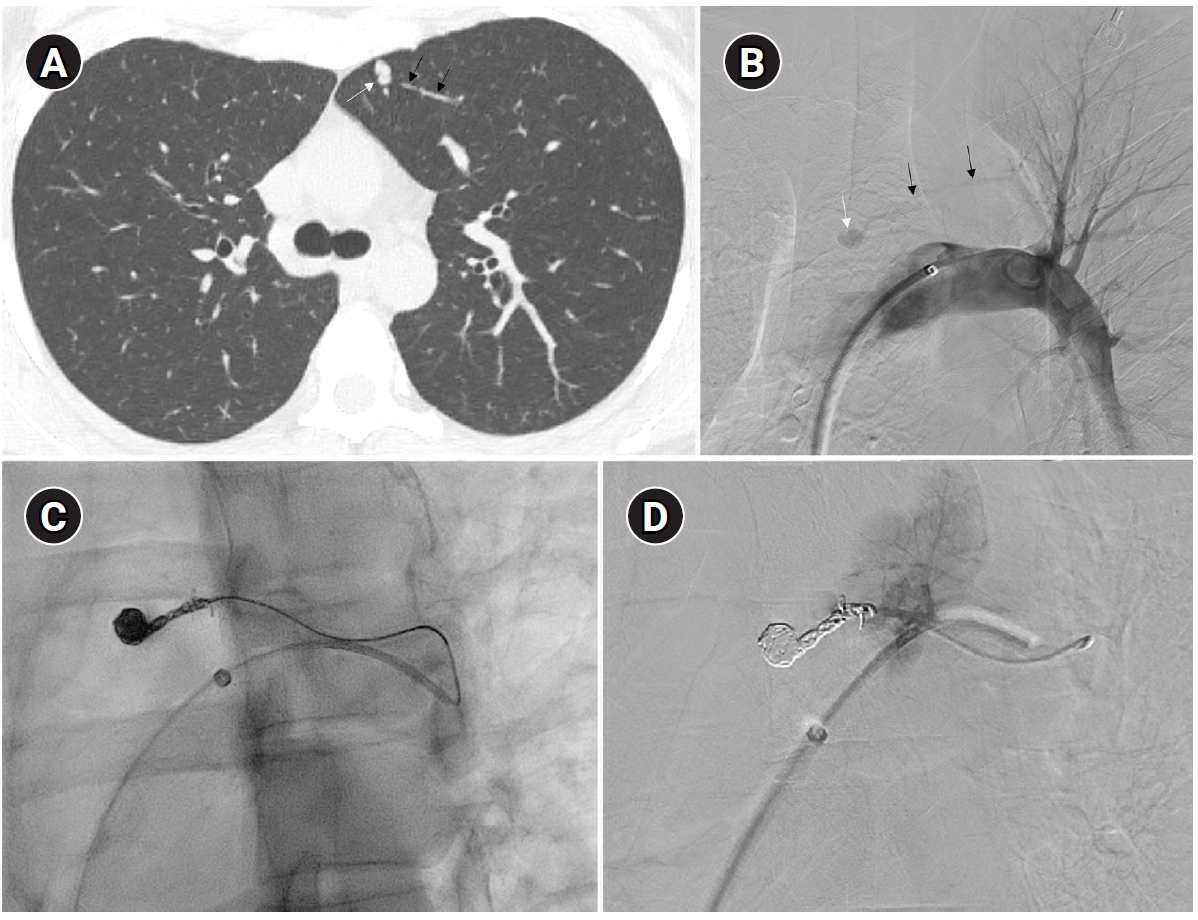

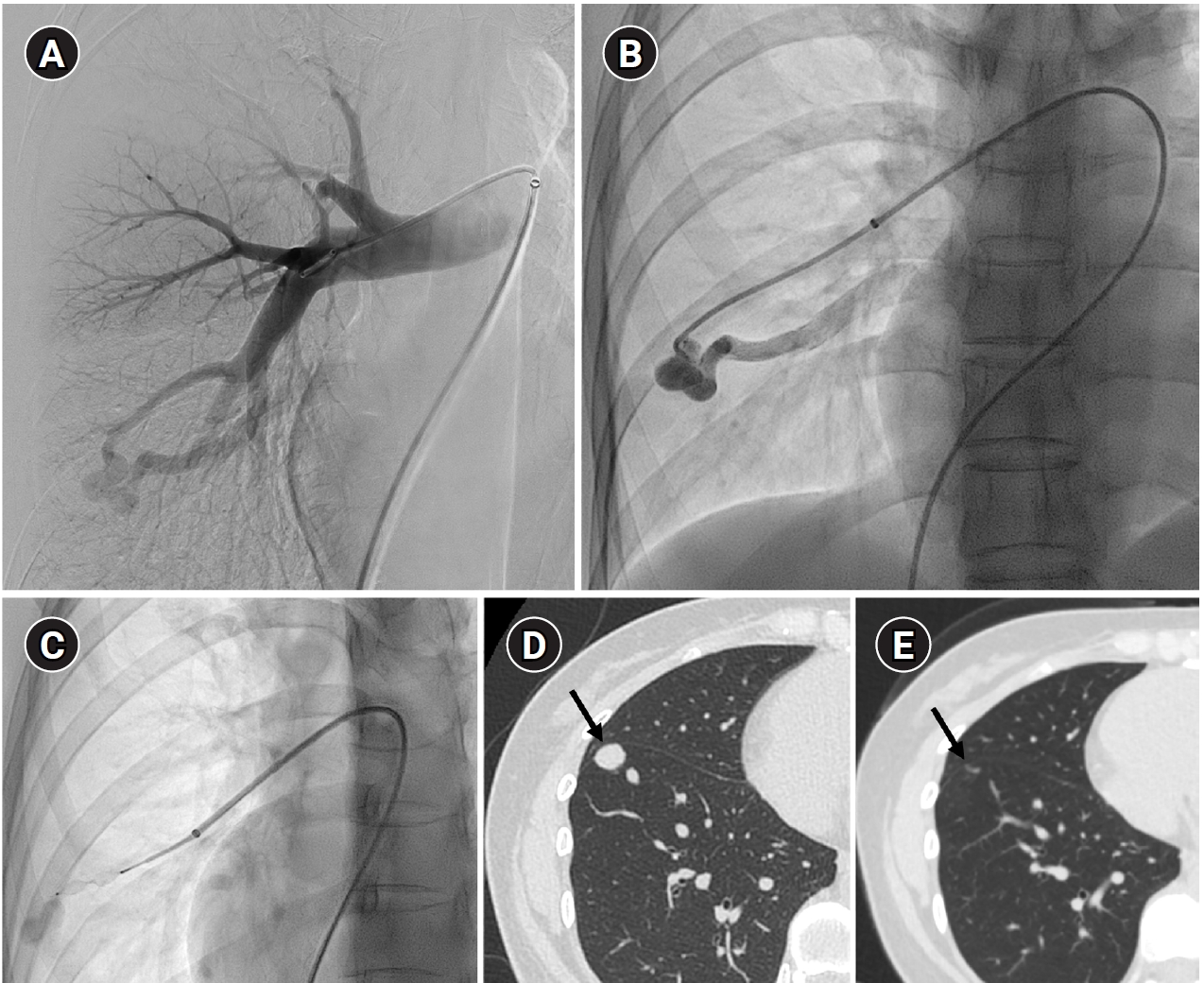

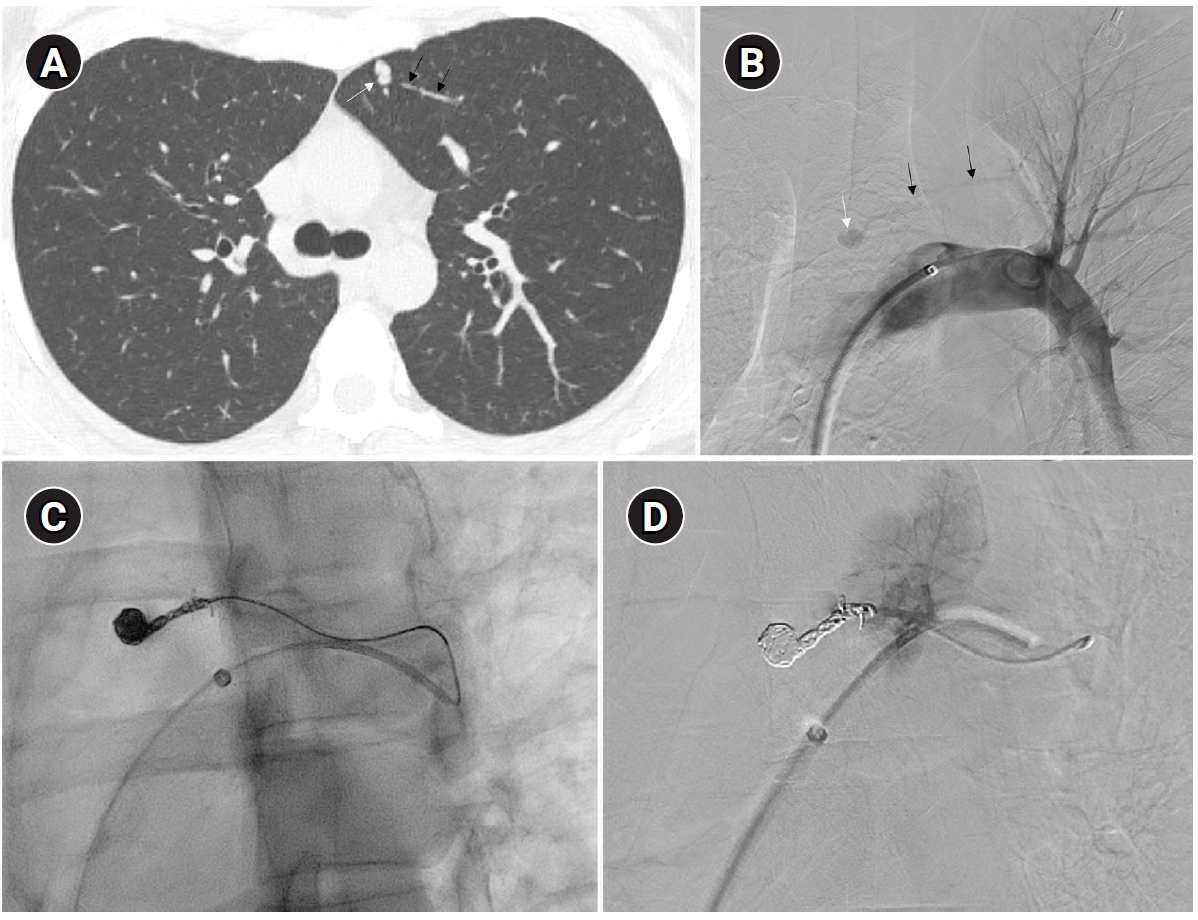

To prevent paradoxical embolism or life-threatening bleeding, all detected PAVMs should be treated in adult patients. Historically, a feeding artery diameter of ‘3 mm’ was considered the minimal diameter criterion for treatment of PAVMs [

2]. However, with advances in embolic devices and catheter systems, less than 3 mm feeding arteries ≥2 mm can now be embolized (

Fig. 2) [

11]. Pregnancy is a special risk factor in patients with PAVM, especially in the second and third trimesters due to a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance and an increase in cardiac output by nearly 50% [

12]. A recent study in 244 pregnant women with HHT showed major complications in 13%, all in patients who had not been screened or treated for PAVMs prior to pregnancy [

13]. Thus, all women with HHT considering pregnancy should be screened for PAVM with computed tomography (CT) and eventually treated prior to conception.

For pediatric patients with PAVMs, it is recommended to treat only if they have symptoms, and if they are asymptomatic or have associated complex anomalies, the approach should be considered on a case-by-case basis [

14]. According to recent studies [

15,

16], PAVMs treated in pediatric patients before puberty show a high recurrence rate because PAVMs may enlarge and evolve with somatic growth, making it difficult to determine the optimal timing for intervention. However, experts suggest that if there are symptoms or if the risk level increases—for instance, when a PAVM is large enough to risk rupture or causes significant hypoxemia—then, it is advisable to treat regardless of age. Otherwise, for asymptomatic PAVMs detected through screening, treatment is recommended after puberty [

10,

11].

Periprocedural Care and Strategies to Minimize Air Embolism

Although the evidence regarding the necessity of intravenous sedation or general anesthesia for the procedure is unclear, in the case of pediatric patients, the procedure typically requires general anesthesia. For PAVM embolization, the right common femoral vein is generally used for access, and intravenous heparin (60–80 units/kg or 3,000–5,000 units) is administered after sheath insertion to prevent catheter-related thrombosis. After sheath insertion, a 7- to 8-Fr vascular sheath is typically used, and long guiding catheters of about 80–90 cm, as well as diagnostic catheters, are employed to access the pulmonary artery via the right atrium. The reason for using a sufficiently long guiding catheter is to reduce catheter exchanges, thereby minimizing arrhythmias and reducing the risk of air embolism. Additionally, it provides more stable support during the embolization procedure, helping to ensure precise placement and control. There is no evidence supporting the use of prophylactic antibiotics for this procedure.

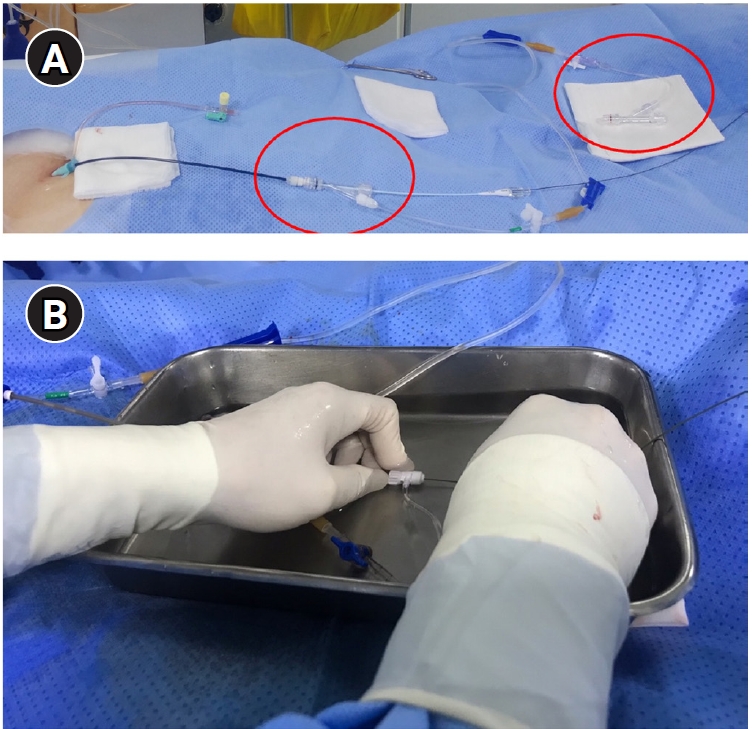

In PAVM embolization, the selection and catheterization of the target feeding artery can be challenging. It is important to analyze the detailed anatomy and branching patterns using pre-procedural CT scans. If fusion imaging is available, incorporating those fused images is also recommended [

17]. In cases such as the right middle lobe or the lingular division of the left upper lobe, where there is a sharp angulation of about 90 degrees, it is important to choose a diagnostic catheter shape that corresponds appropriately. If the feeding artery is identified, a guidewire or microcatheter can be used to approach the feeding artery more closely. This allows advancement of a 4- or 5-Fr catheter or guiding sheath deeper into the feeding artery, improving stability during embolization. Special caution is required to prevent air embolism and intraprocedural thrombus formation. To minimize the risk of thromboembolism, meticulous heparinized saline flushing using a rotating Y-connector is essential. At the author’s institution, two separate heparinized saline flushing systems (5,000 U of heparin mixed with 500 mL of saline) are routinely prepared: one for the 6-Fr guiding sheath and another for flushing 4- or 5-Fr catheters. These systems can be connected between the diagnostic catheter and the microcatheter or the Amplatzer vascular plug adaptor to ensure continuous flushing and reduce the risk of air or thrombus introduction. Special caution is required to prevent air embolism. To prevent air embolism, it is important to use a heparinized saline flushing technique with a rotating Y-connector. Additionally, performing guidewire or coil insertion and exchanges under a water seal, essentially submerged in fluid, can also be helpful (

Fig. 3). During the procedure, when injecting contrast material—particularly into the feeding artery—it is essential to aspirate blood and confirm that all air has been completely removed from the catheter. This is especially important when accessing small-caliber feeding arteries, as the catheter tip may become wedged within the vessel lumen, increasing the risk of air being introduced or trapped inside the catheter. When air embolism occurs, issues can arise mainly if the air enters the coronary arteries or the cerebral circulation. If an air embolism occurs in the heart, the patient may experience sudden-onset chest discomfort and difficulty breathing, which usually improves with conservative management such as providing oxygen.

Embolic Materials and Techniques

Historically, detachable balloons were used as an embolization material; however, they are no longer utilized in current practice [

18]. In the context of PAVM embolization, the use of coils, vascular plugs, or a combination of both is now standard practice [

19-

21]. Since the development of detachable coils, they have offered advantages over pushable coils, particularly in terms of repositioning during the procedure. They can even be fully retrieved and redeployed if necessary, enhancing procedural safety and control. It is crucial to prioritize minimizing the recanalization rate while ensuring the overall safety of the procedure when selecting the appropriate embolic materials and techniques. Feeding artery coil embolization was historically regarded as the standard approach, whereas venous sac embolization was discouraged because of the perceived risk of rupture [

22]. However, with the introduction of newer venous sac embolization techniques, recent findings now indicate that tightly packing the venous sac with coils can achieve a higher success rate than the traditional feeding artery approach (

Fig. 2) [

22-

25]. Additionally, vascular plugs, including micro-vascular plugs (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Amplatzer vascular plugs (Abbott Vascular, Saint Paul, MN, USA) have also demonstrated a higher success rate compared to feeding artery coil embolization (

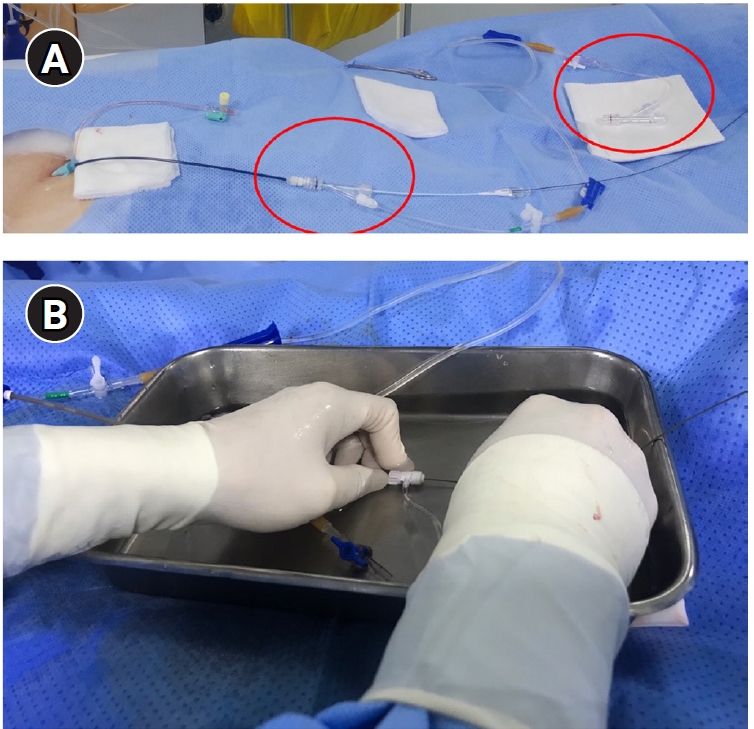

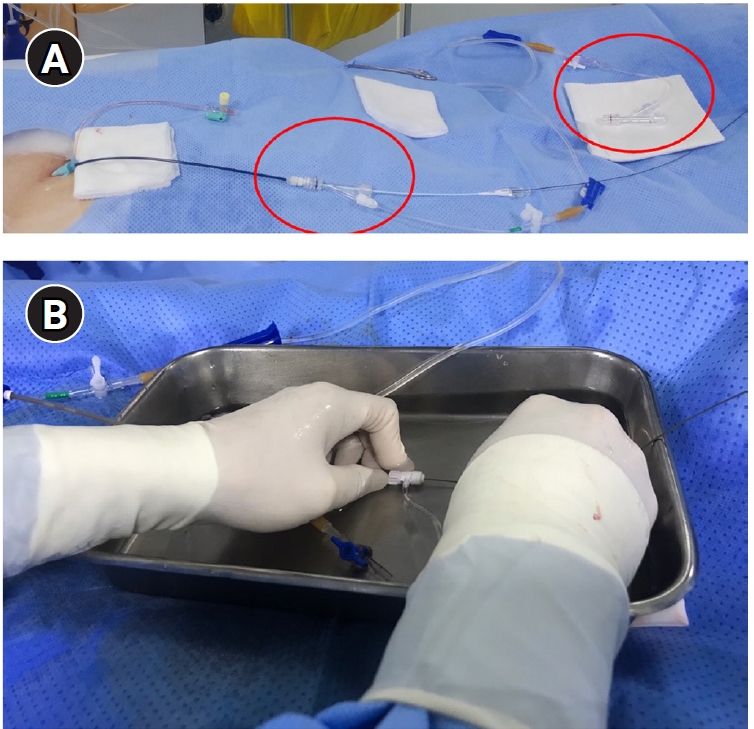

Fig. 4) [

26-

28]. In the case of vascular plugs, the risk of device migration is relatively low. Moreover, an additional advantage is that the device can be repositioned if the sizing is not ideal or if it is not deployed in the exact desired location. This flexibility enhances the precision of the procedure (

Fig. 5). In a recent European guideline, there is also a recommendation to consider vascular plug embolization as a first-line option whenever possible, rather than coil embolization [

11]. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis recommended vascular plugs or venous sac coil embolization, noting that vascular plugs had a recanalization rate of 13.6% compared to 32.7% for coil-only embolization. Similarly, venous sac embolization showed a 3.8% recanalization rate, while feeding artery embolization had a rate of 24.3%. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis has recommended the use of vascular plug or venous sac coil embolization, as these techniques have demonstrated a lower persistence rate compared to other methods [

21]. This shift is largely in response to the relatively high recanalization rate associated with feeding coil embolization. In the case of embolization using vascular plugs, the plug should be deployed at the most distal segment of the feeding artery just before the venous sac in order to preserve the normal pulmonary artery. Since the pulmonary artery contains less elastin and has a thinner wall compared to systemic arteries, it is more distensible [

29]. Therefore, in the author's experience, oversizing by about 50% to 100% has been effective in reducing the recanalization rate. When performing venous sac coil embolization, it is important to use coils large enough to create a stable framing coil larger than the draining vein diameter, thereby preventing coil migration. After establishing this frame, the venous sac and the proximal feeding artery should be carefully packed to achieve complete occlusion.

Procedure-Related Complications

The most common complication during PAVM embolization is pleuritic chest pain [

1]. In addition, transient arrhythmias may occur due to intracardiac catheter manipulation, although these are typically self-limiting. A small amount of air may also be inadvertently introduced during the procedure, potentially leading to acute chest discomfort or dyspnea. Such symptoms are usually transient and can be managed with intravenous nitroglycerin or atropine, resolving spontaneously as the air is absorbed. Additionally, patients may experience arrhythmias caused by intracardiac catheterization during the procedure, but these are typically self-limiting. A small volume of air can be introduced during the procedure, which typically enters the coronary arteries and may cause sudden-onset chest discomfort or dyspnea. In such cases, this can be managed with intravenous nitroglycerin or atropine, and it generally resolves once the air is absorbed without significant issues [

30]. In contrast, device-related complications primarily include migration of embolic materials into the pulmonary vein. Given that the pulmonary vein generally has a larger diameter than the corresponding pulmonary artery, appropriate device sizing is essential. The use of a framing coil larger than the draining vein diameter or an adequately oversized vascular plug is recommended to minimize the risk of device migration. In addition, continuous flushing with heparinized saline helps prevent thrombus formation within the catheter. To prevent these complications, it is advisable to use the framing coil or an appropriately oversized plug to prevent device migration into the pulmonary vein. Additionally, flushing through a heparinized saline line can help prevent thrombus formation within the catheter. Pulmonary parenchymal hemorrhage can occur due to the device or catheter, and it is usually self-limiting, often accompanied by mild hemoptysis. In cases where the device causes pulmonary artery perforation, quickly occluding the feeding artery with an appropriate embolic material can reduce further complications such as hemothorax [

31].

Surveillance after Embolization

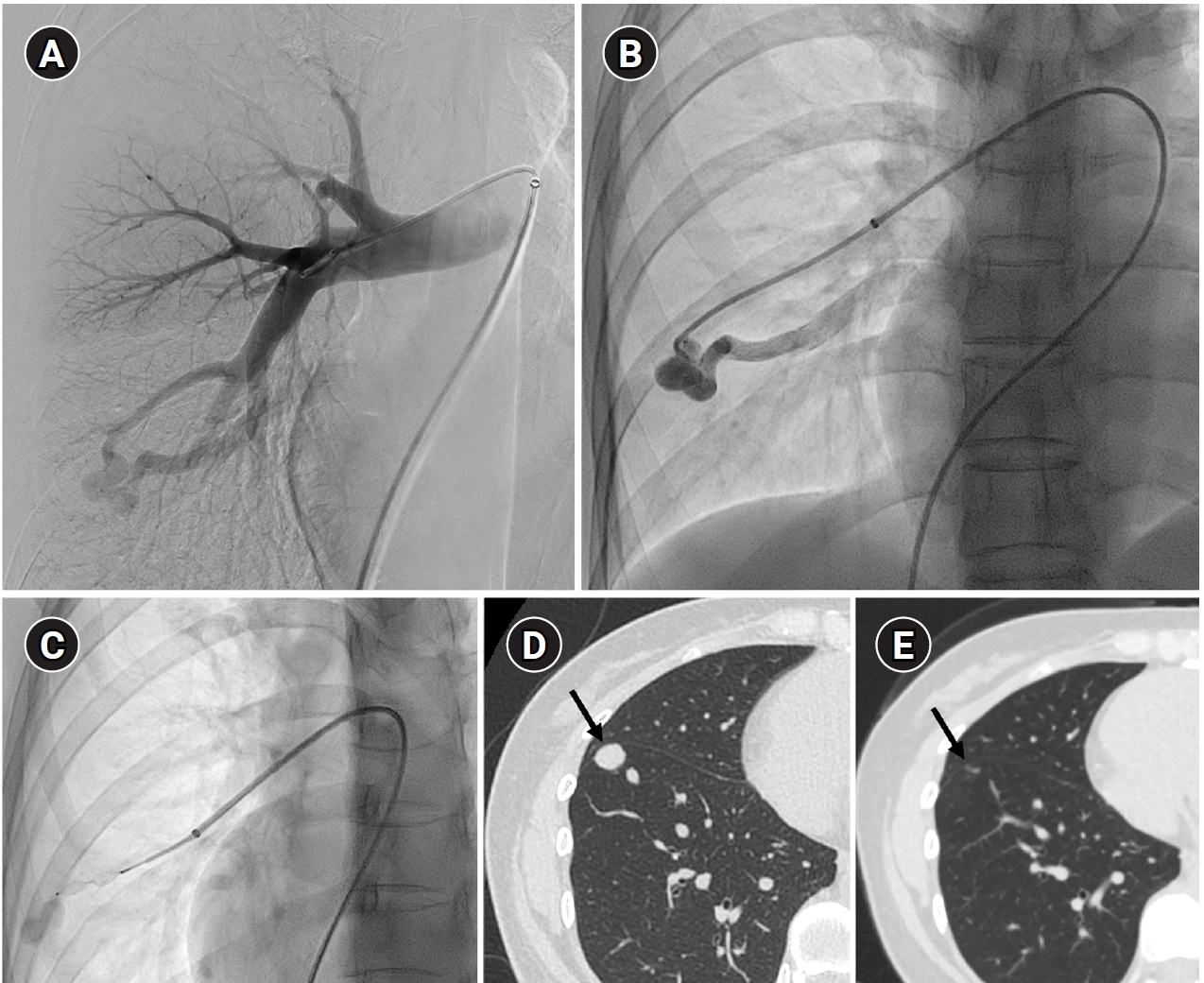

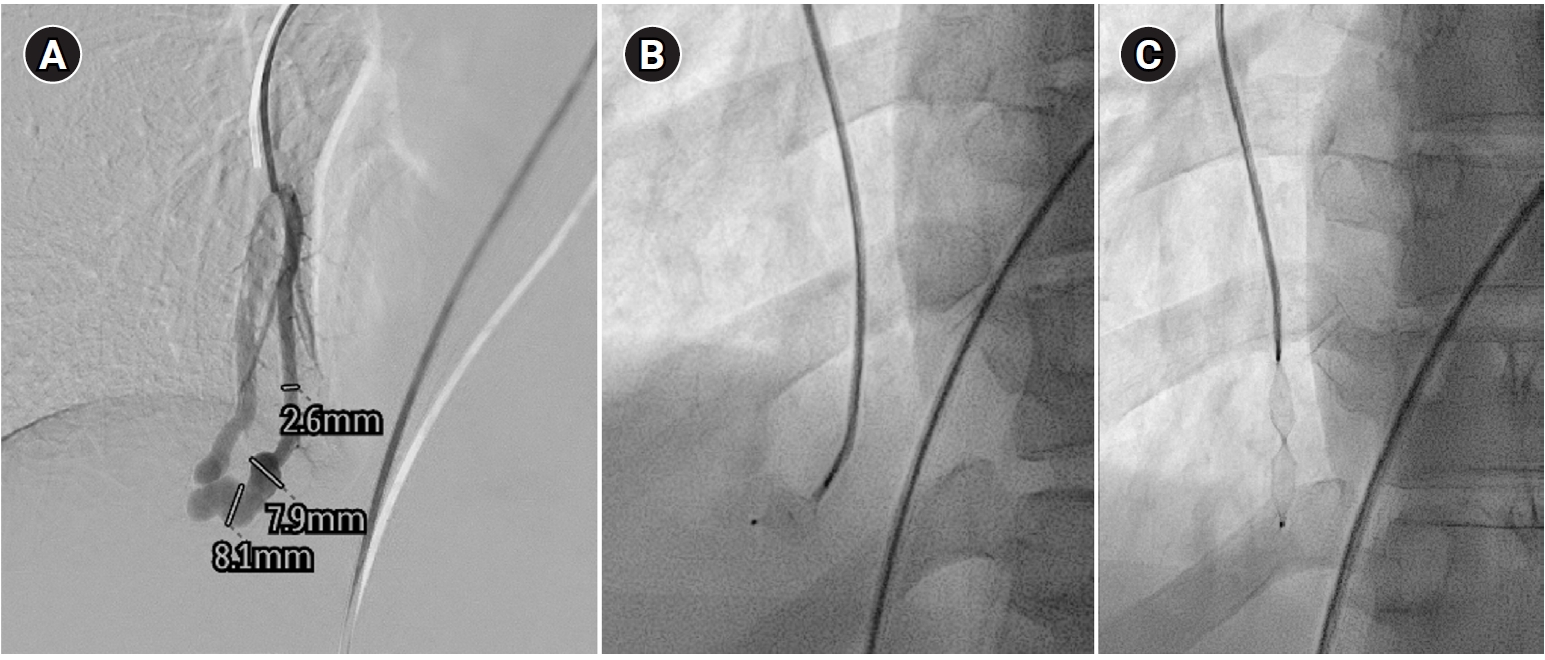

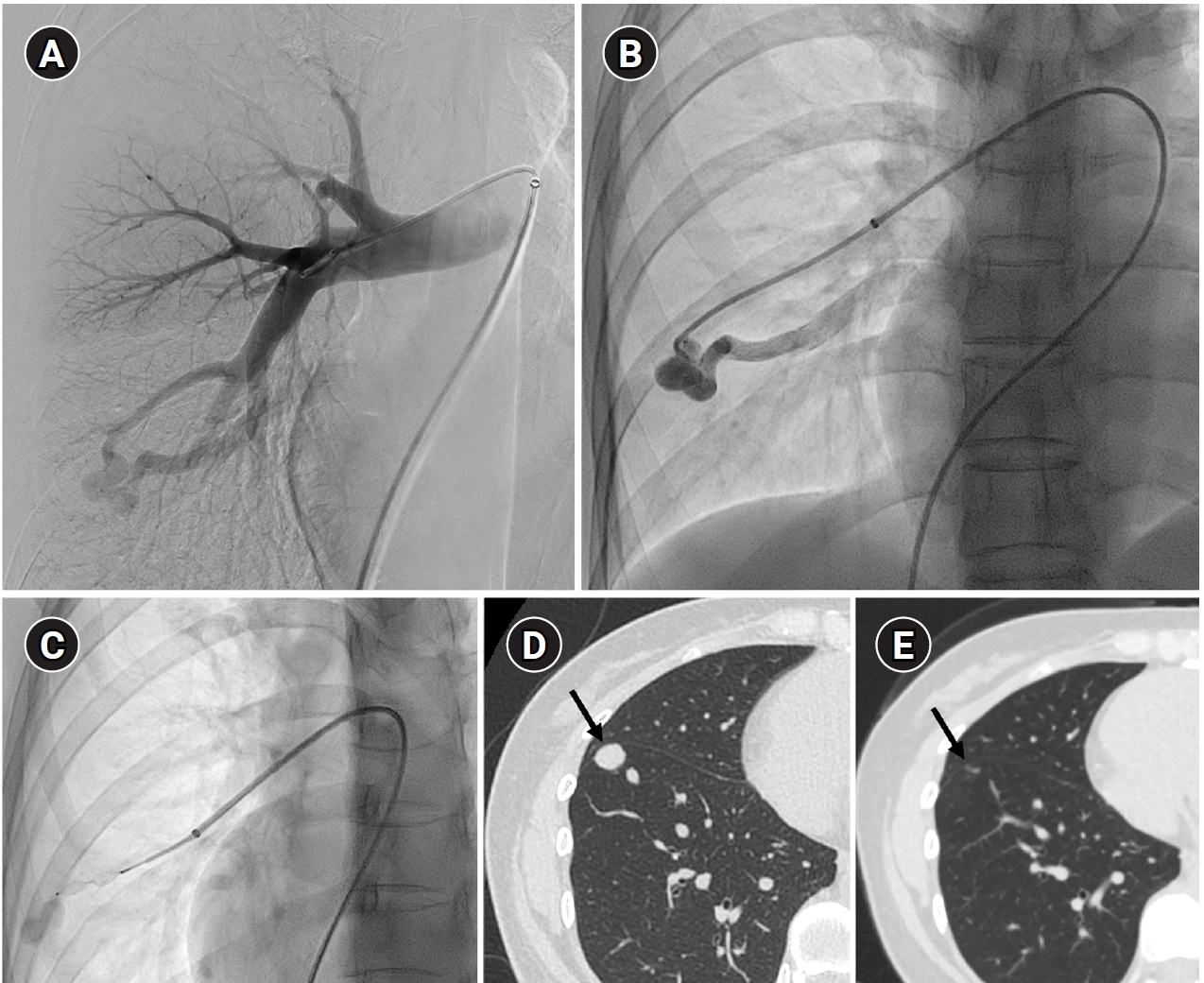

Long-term follow-up after treating PAVMs is needed to detect newly developed PAVMs and to identify persistence or recurrent flow [

10,

11]. Treatment failure in PAVMs can be classified as recanalization and reperfusion. Recanalization refers to the reopening of blood flow through spaces between the previously placed embolic material (

Fig. 6). Reperfusion, on the other hand, occurs when blood flow from an adjacent pulmonary artery reopens the previously embolized distal vein or venous sac (

Fig. 7) [

32]. As the primary follow-up modality, CT is recommended, but there are currently no specific guidelines on whether or not to use contrast enhancement [

33]. It is recommended to perform an initial evaluation by CT about 6 months after PAVM embolization, and then follow-up with CT every 3–5 years thereafter (

Fig. 8). In CT follow-up, the evaluation is based on the reduction rate of the venous sac or the draining vein, and the traditional criterion is that there should be at least a 70% reduction in the size of the venous sac or draining vein [

34,

35]. In recent studies, there have been opinions that this 70% size reduction criterion is too strict. In response, some research using angiographic-confirmed cases or time-resolved magnetic resonance angiography (TR-MRA) has proposed a 50%–60% guideline [

36,

37]. When using CT, repeated radiation exposure and metal artifacts from the coils can be problematic. By using metal artifact reduction techniques, it is possible to obtain clear images of the surrounding parenchyma, and this also helps in assessing parameters like the draining vein diameter reduction rate (

Fig. 9) [

38]. Furthermore, low-dose CT protocols may help reduce cumulative radiation exposure during repeated follow-up imaging.

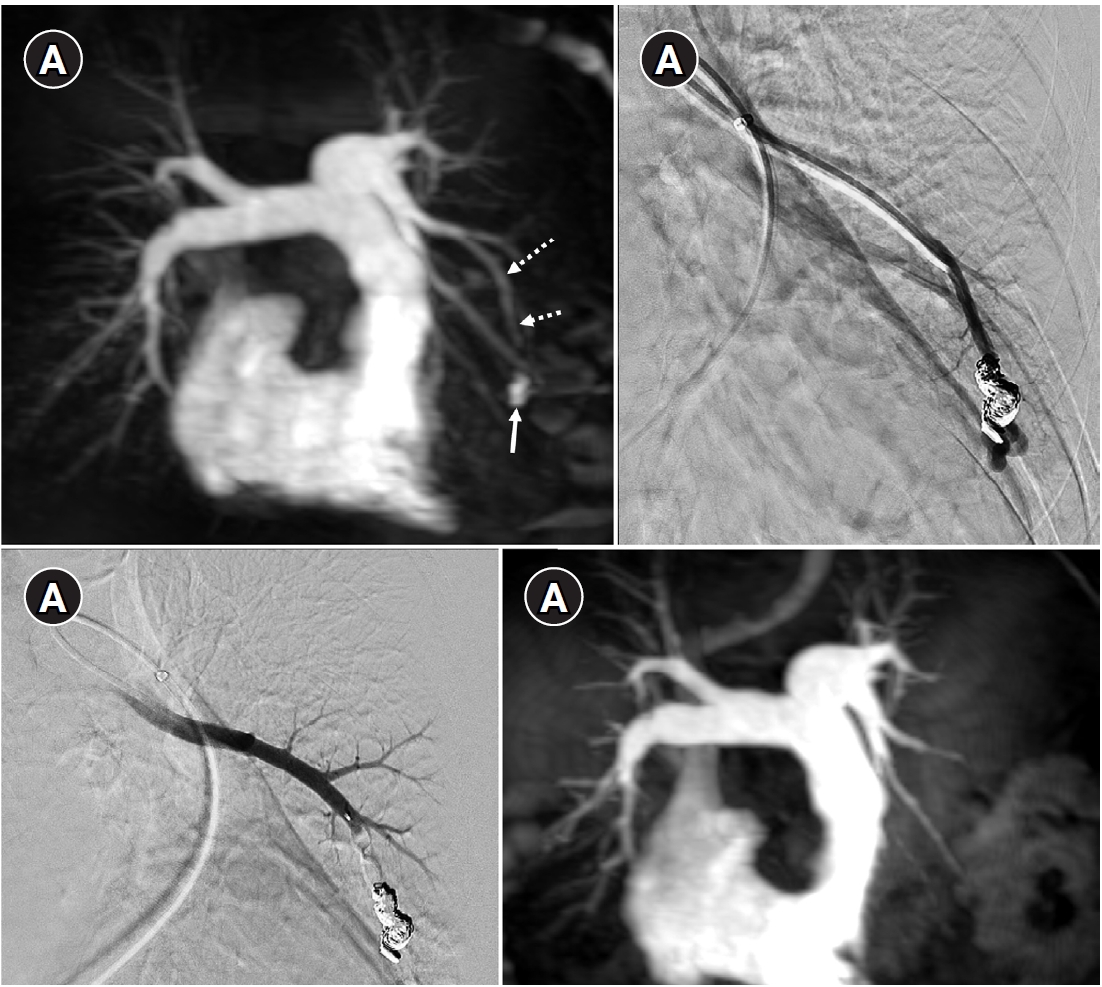

In parallel, increasing attention has been directed toward the role of dynamic imaging modalities, particularly TR-MRA [

39-

42]. Reperfusion can be confirmed if the draining vein is observed simultaneously with the pulmonary artery on TR-MRA. Because TR-MRA can clearly distinguish between the pulmonary arterial and pulmonary venous phases, and because it is less affected by coil artifacts, it allows for a more reliable differentiation between residual arteriovenous malformation and residual sac filling caused by normal pulmonary vein drainage (

Fig. 10) [

41].

Conclusion

Endovascular embolization remains the cornerstone of treatment for PAVMs, offering effective prevention of paradoxical embolism and hemorrhagic complications when appropriately performed. Ongoing advances in embolic materials and techniques—particularly the use of vascular plugs and venous sac embolization—have significantly improved treatment durability by reducing recanalization and persistence rates.

A thorough understanding of PAVM anatomy, careful procedural planning, and meticulous attention to periprocedural techniques are essential to minimize complications such as air embolism, device migration, and vascular injury. Long-term surveillance is equally critical, as treatment failure may occur through either recanalization or reperfusion. In this context, evolving imaging strategies, including metal artifact–reduced CT and TR-MRA, provide valuable tools for accurate post-treatment assessment while mitigating limitations of conventional imaging.

As evidence continues to evolve, individualized treatment strategies that balance procedural safety with long-term efficacy are paramount. An interventional radiologist–centered, evidence-based approach is essential for optimizing outcomes in patients with PAVMs, particularly those with HHT who require lifelong surveillance and management.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

None.

Author contributions

The author conducted all aspects of the study.

Data availability statement

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

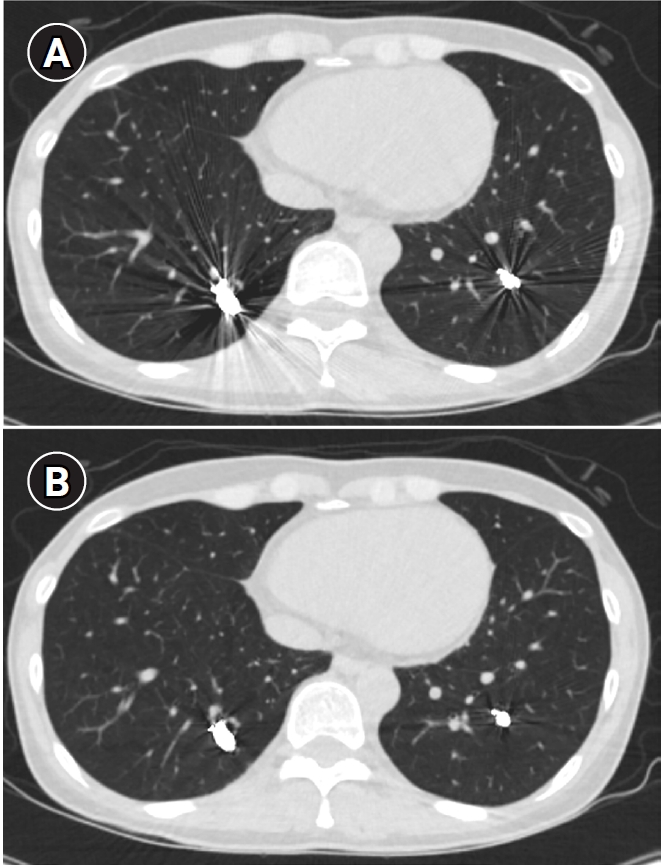

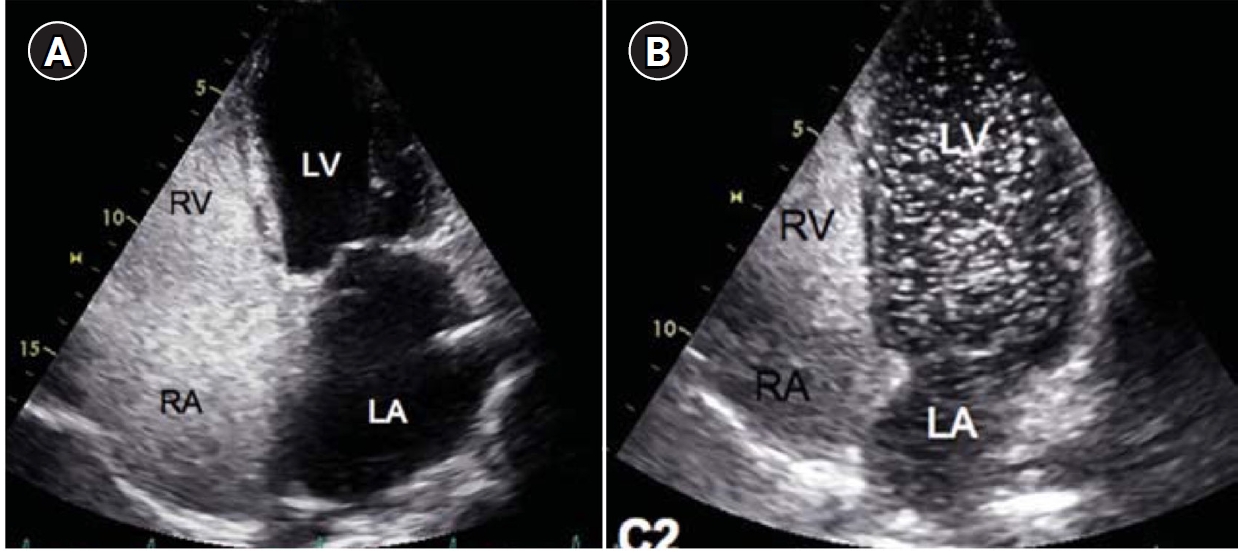

Fig. 1.Agitated saline bubble echocardiography images. (A) After injection of agitated saline bubbles into a peripheral vein, echogenic bubbles are seen filling the right heart. Under normal conditions, the bubbles are completely filtered by the pulmonary capillary bed, and no bubbles appear in the left cardiac chambers. (B) After the appearance of bubbles in the right cardiac chambers, bubbles are subsequently observed in the left cardiac chambers after three cardiac cycles, indicating the presence of an extracardiac shunt (pulmonary arteriovenous malformation). RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle.

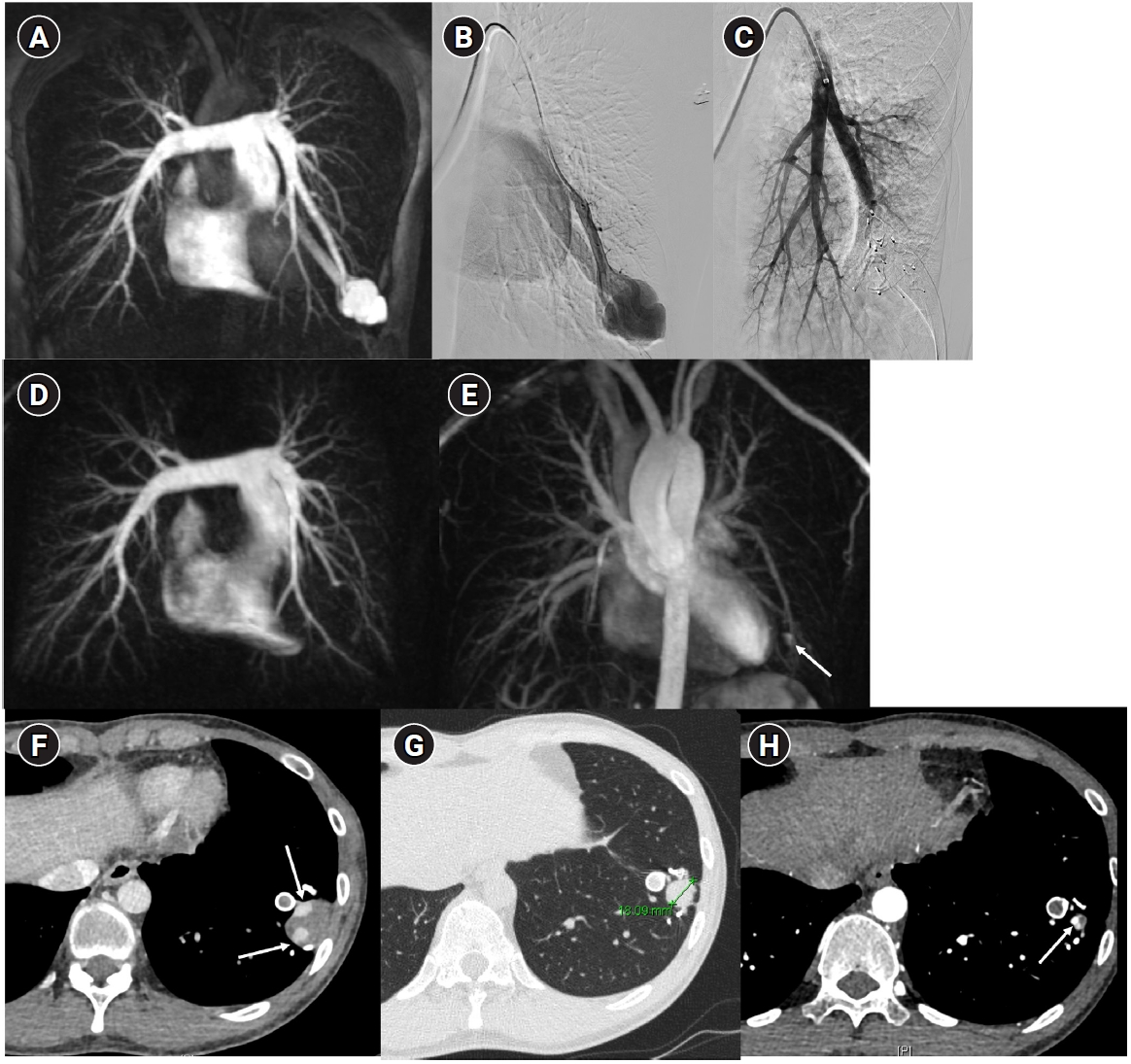

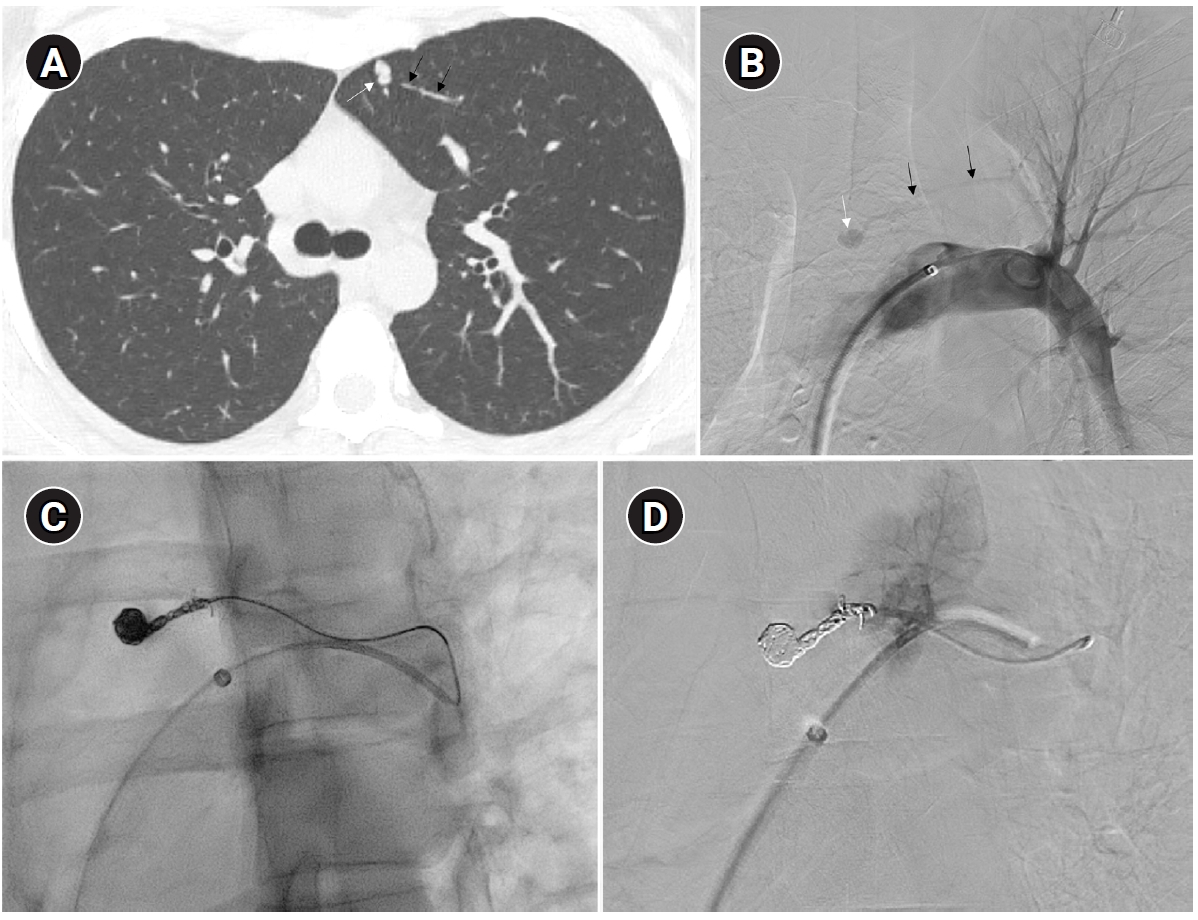

Fig. 2.Embolization of a 1.5-mm feeding artery associated with an arteriovenous malformation in the left upper lobe of a 36-year-old female patient. (A) On the computed tomography (CT), a slender 1.5 mm feeding artery to the left upper lobe (black arrows) and a dilated venous sac (white arrow) are visible. (B) On angiography, the same finding as on the CT is observed (black arrows and white arrow), (C, D) A scene of coil embolization (C) and a post-embolization angiography image (D). In panel (D), the tri-axial system was utilized, including a 6-Fr Shuttle guiding catheter, a 5-Fr angled catheter, and a 1.9-Fr microcatheter, to access the feeding artery. Coil embolization was performed using Concerto 3D and Helix coils.

Fig. 3.Techniques to prevent air embolism and intracatheter thrombosis during pulmonary arteriovenous malformation procedures. The illustration demonstrates the use of two rotating Y-connectors (red circles) with heparinized saline flushing (A) one for guiding catheter and another for 5-Fr catheter, as well as underwater insertion techniques (B) to minimize the risk of air embolism and catheter-related thrombosis. Note, second flushing line is connected to vascular plug adaptor (arrow).

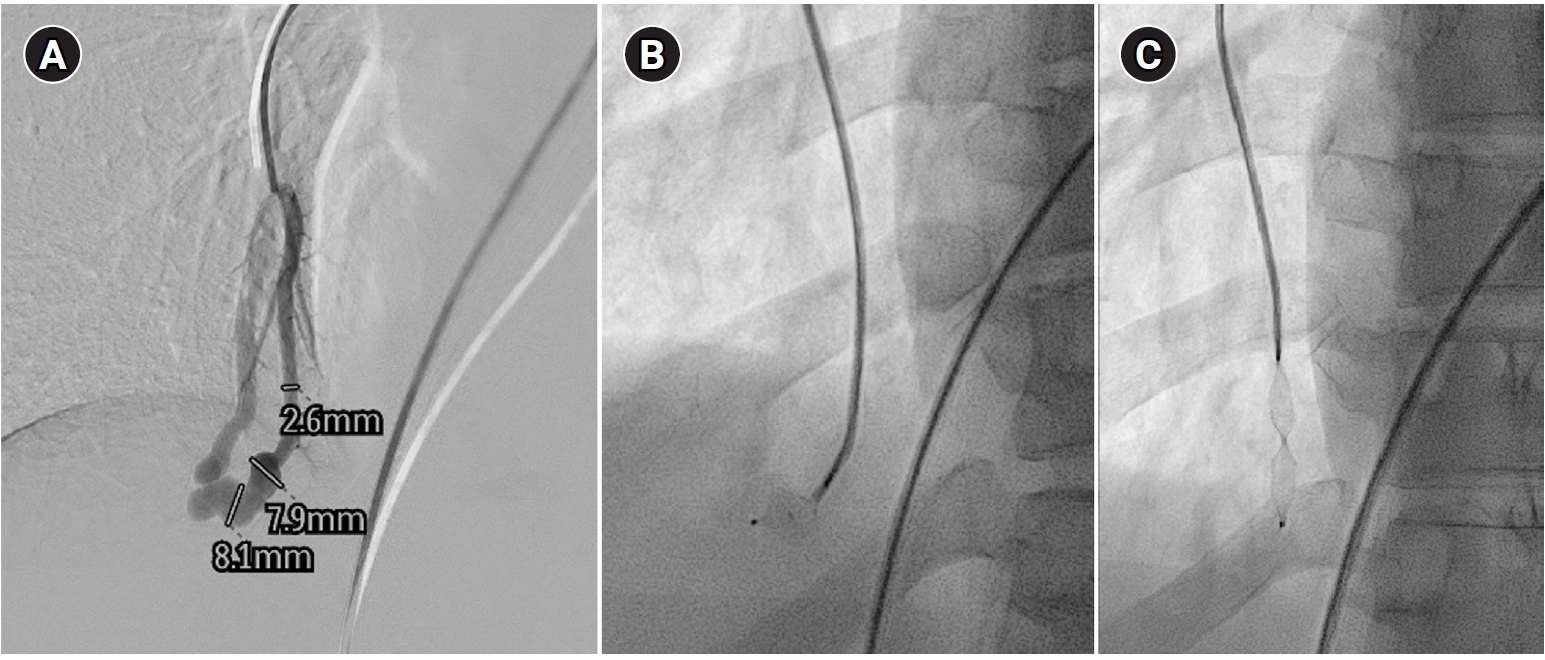

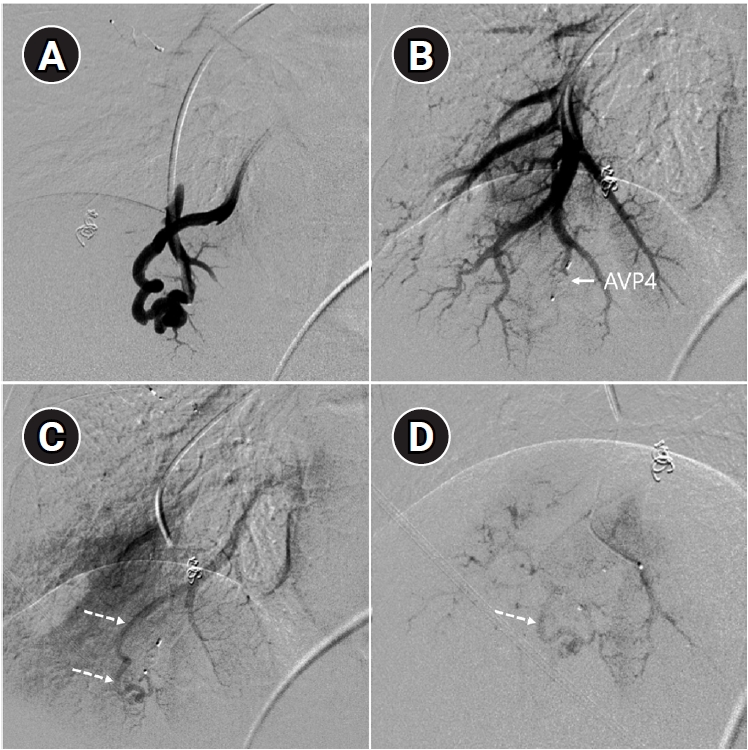

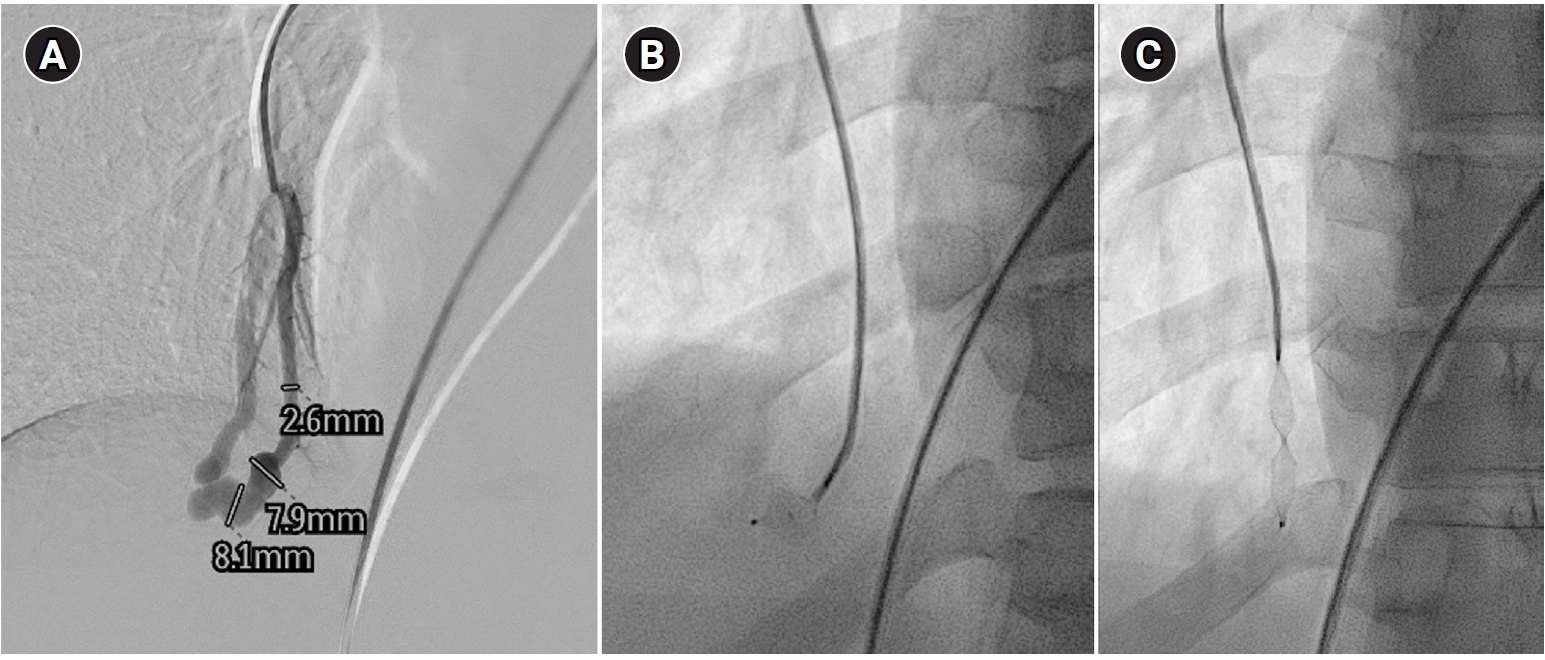

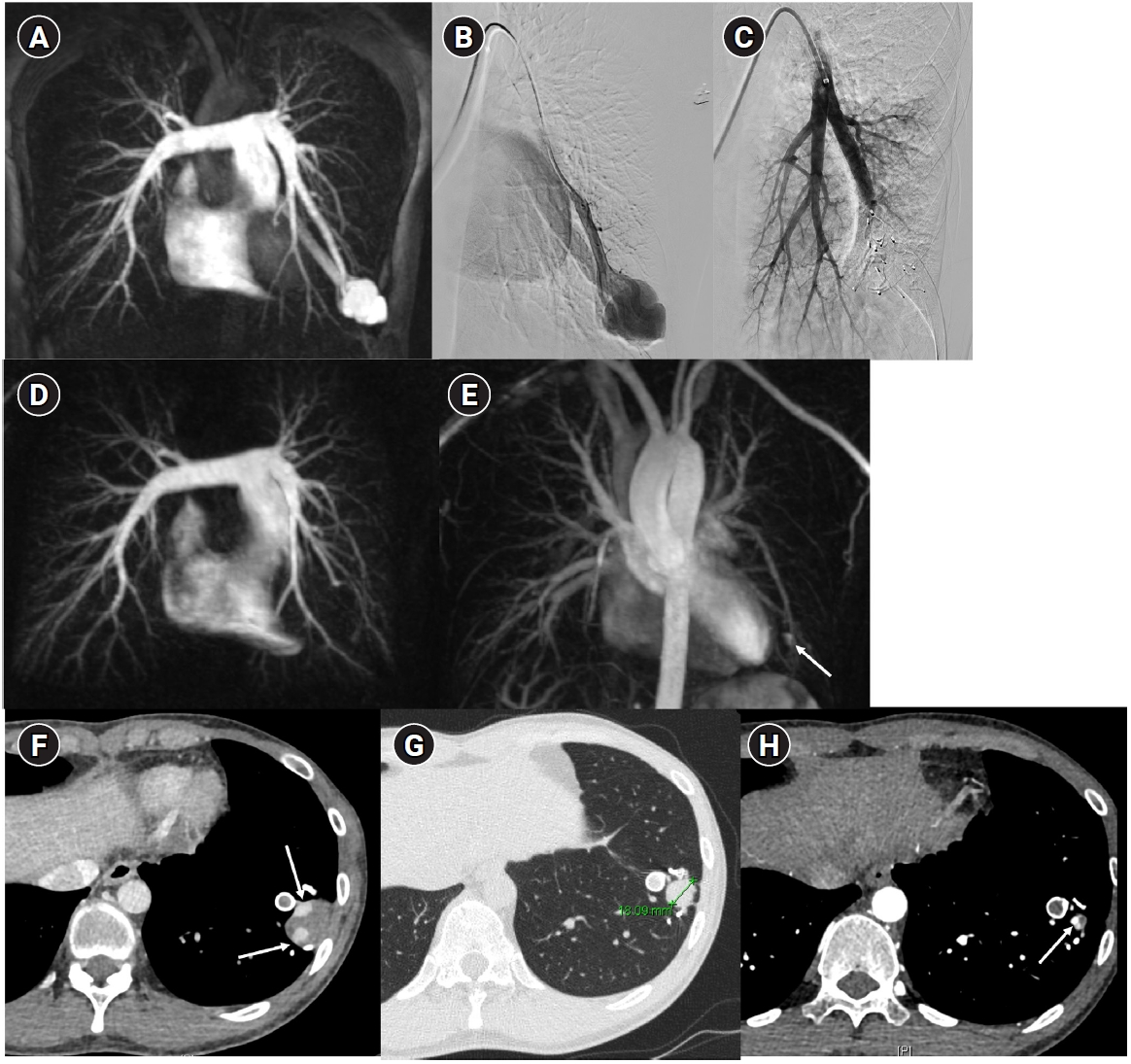

Fig. 4.The images show a 38-year-old female patient undergoing pulmonary arteriovenous malformation embolization using an Amplatzer vascular plug. (A) A simple pulmonary arteriovenous malformation is observed in the right pulmonary angiography, and the feeding artery diameter is measured at 3.7 mm. (B) An 8-Fr, 80-cm guiding catheter and a 5-Fr Berenstein angled catheter were used to advance to the distal end of the feeding artery. (C) A 7-mm Amplatzer vascular plug type IV (arrow) was deployed at the distal portion of the feeding artery with a 100% oversizing. (D, E) The large venous sac (arrow) that was visible on the pre-procedure non-enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) (D) had only a trace remaining (arrow) on the CT performed 6 months later (E).

Fig. 5.Embolization procedure in a patient with a feeding artery diameter of 2.6 mm and a venous sac diameter of 8 mm in the right lower lobe. (A) Selective angiography of the right lower lobe pulmonary arteriovenous malformation. (B) A 7 mm Amplatzer vascular plug type IV (arrow) was deployed into an approximately 8 mm venous sac, and it was determined that this would not provide adequate embolization effect. (C) By repositioning the Amplatzer plug and deploying it at the distal part of the feeding artery (arrow), it becomes clear that an Amplatzer vascular plug sufficiently larger than the feeding artery’s size is needed to effectively achieve embolization.

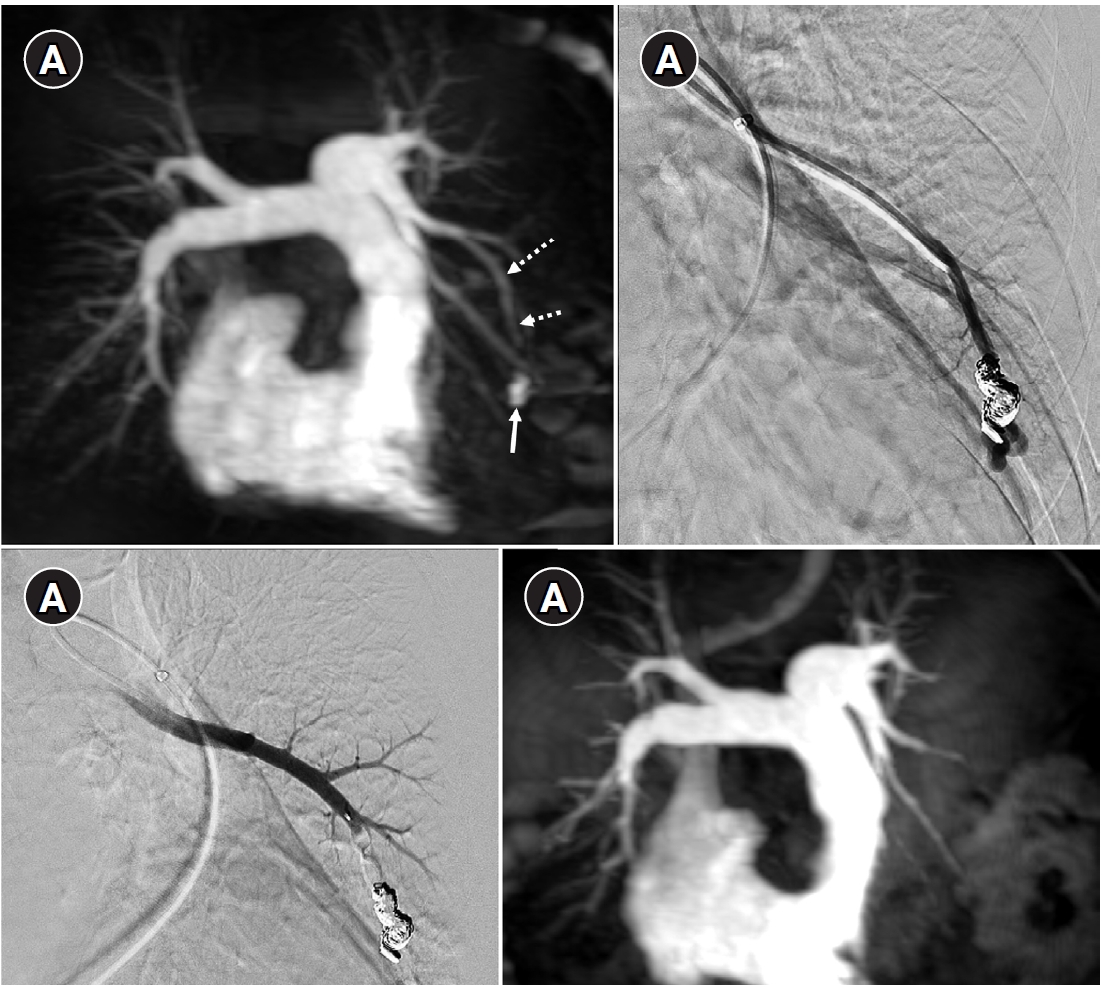

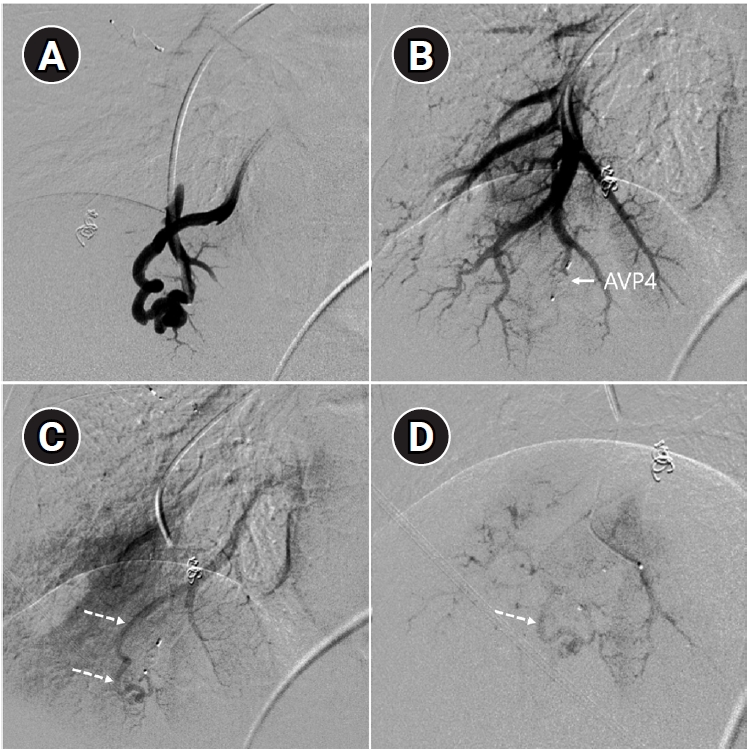

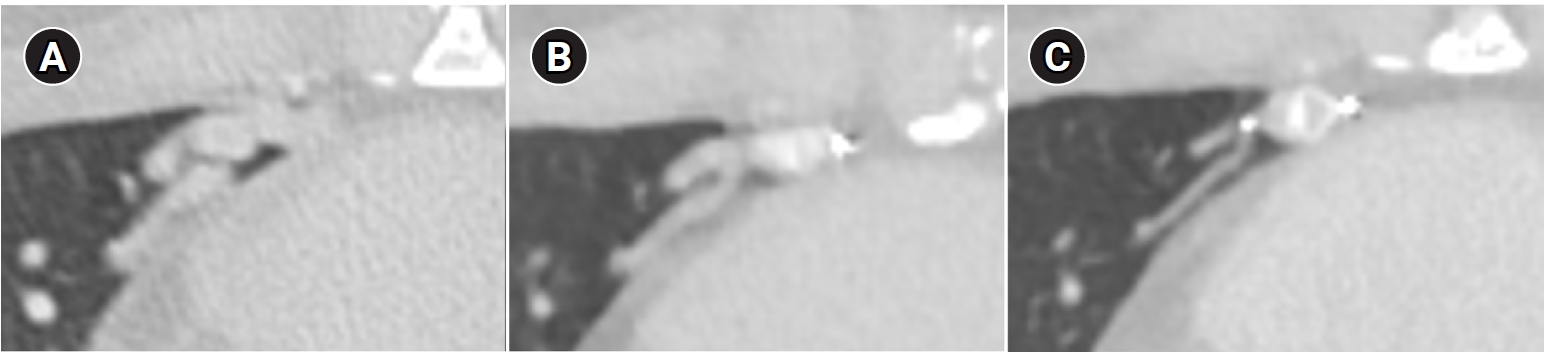

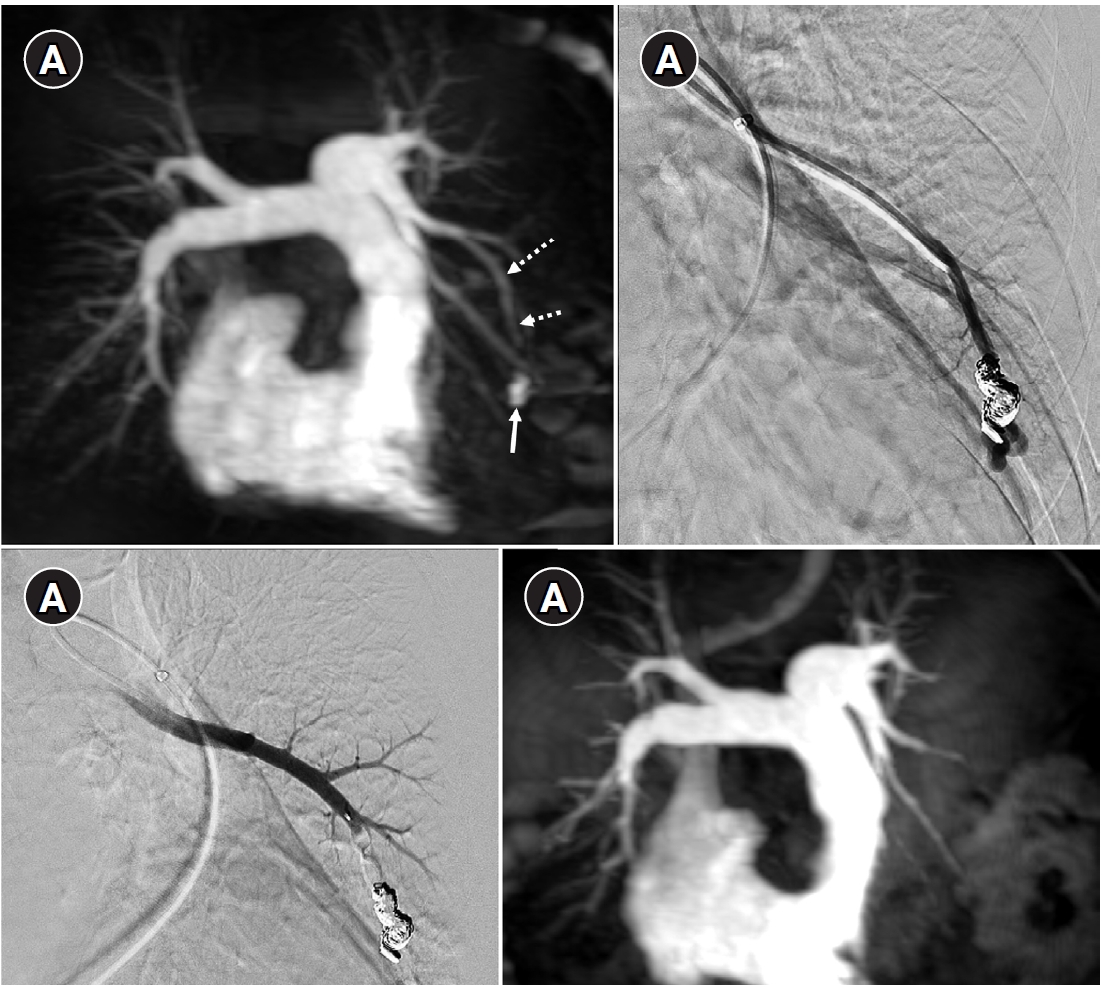

Fig. 6.Time-resolved magnetic resonance angiography (TR-MRA) and procedural images of a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation showing recanalization. (A) In the TR-MRA performed before the procedure, a venous sac (arrow) is observed concurrently with the feeding artery (dashed arrows). (B) Recanalization was confirmed in the selective angiography. (C) Utilizing additional coils and an 8 mm Amplatzer vascular plug type IV (AVP 4) (arrow), the feeding artery embolization was carried out. (D) On the 6-month follow-up TR-MRA, the feeding artery is no longer visible, and the venous sac is also not observed.

Fig. 7.Example of a patient showing reperfusion after pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) embolization using an Amplatzer vascular plug type IV (AVP 4). (A) Angiography of a simple-type PAVM in the right lower lobe accessed with a 5-Fr catheter. (B) Early pulmonary arterial phase image from a diagnostic angiography performed three years later due to suspected reperfusion on follow-up computed tomography, showing that the pulmonary vein is not visible distal to the AVP 4 (indicated by the arrow). (C) Delayed phase image confirming the pulmonary vein, marked by dashed arrows, which corresponds to the venous sac and draining vein seen in (A), now reduced in size. (D) A typical example of reperfusion shown on angiography using a microcatheter in an adjacent pulmonary artery, illustrating multiple newly formed tortuous collaterals leading to the draining vein (marked by dashed arrows). In this patient, additional AVP 4 embolization was performed at the tip of microcatheter (black arrow). However, draining vein size persisted even after additional treatment (not shown).

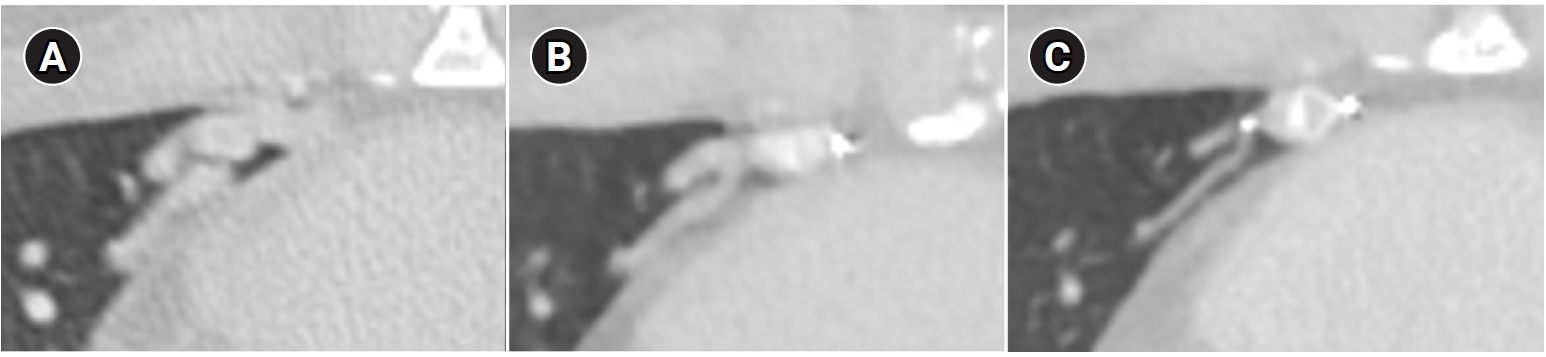

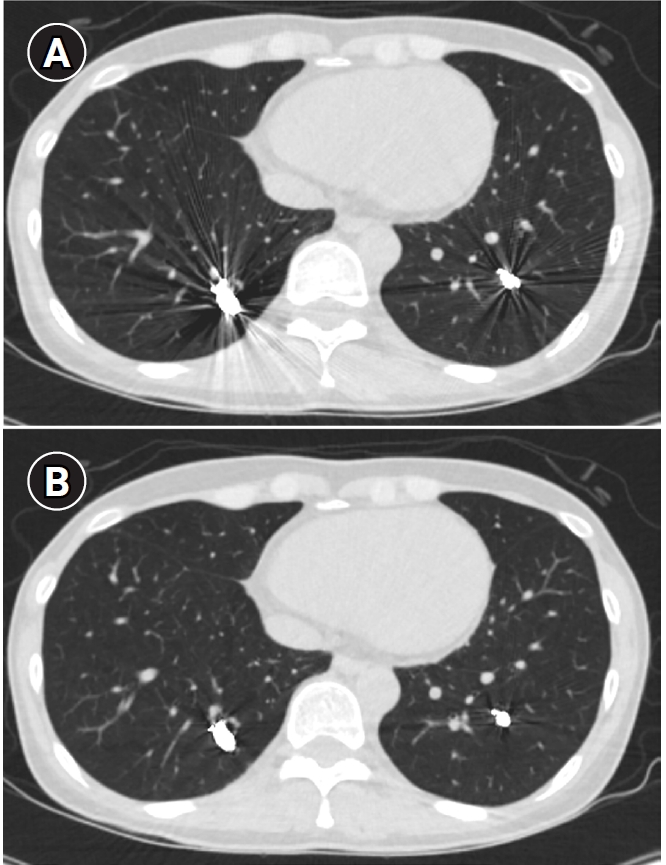

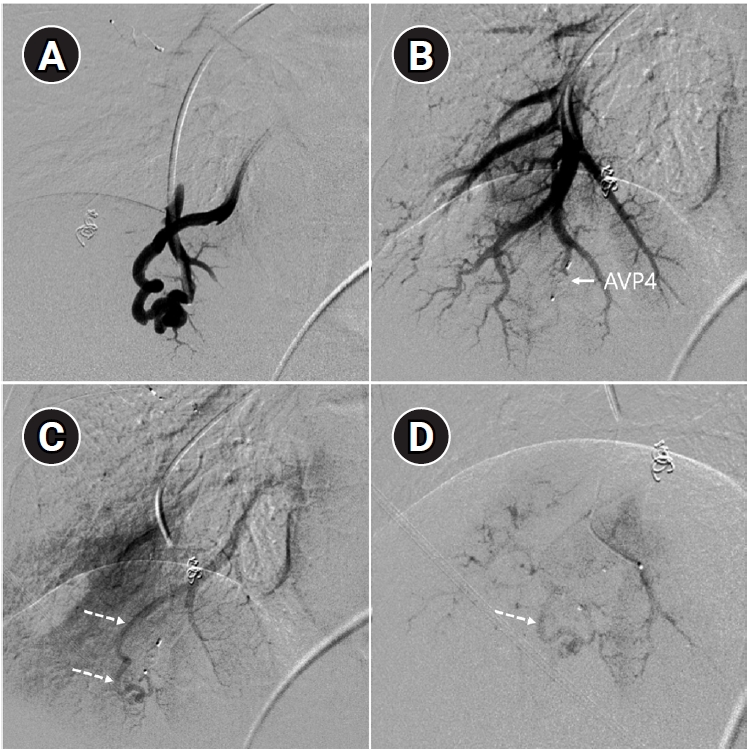

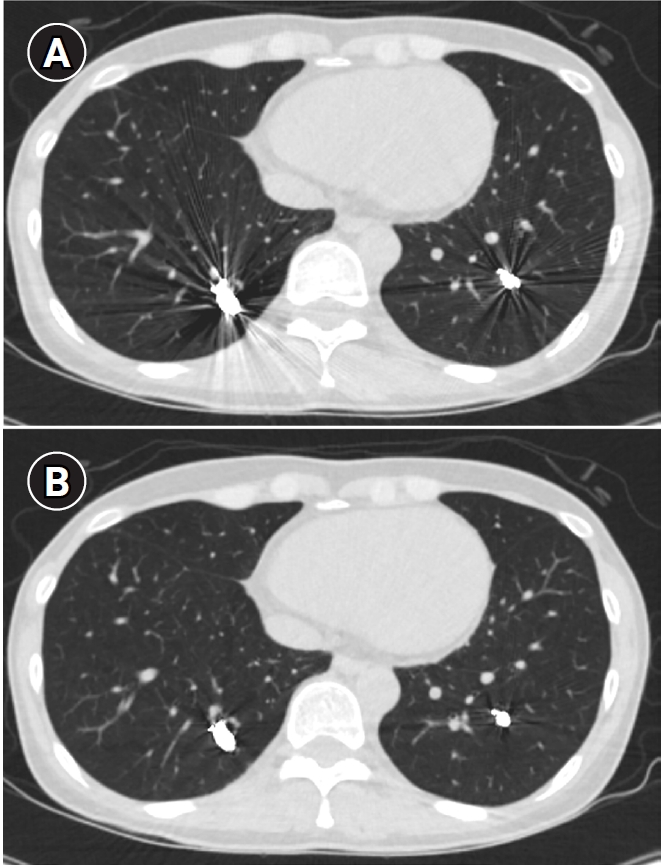

Fig. 8.Computed tomographic (CT) images of a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation before the procedure (A), 20 days after embolization (B), and at the 6-month follow-up (C). After the procedure, at both 20 days and 6 months, the diameter of the feeding artery and the draining vein is gradually reduced. In this case, the embolization was performed using an Amplatzer vascular plug type IV. Notably, the Amplatzer vascular plug produces minimal beam-hardening artifacts on CT, aiding in the evaluation of vessel diameter and the surrounding parenchyma.

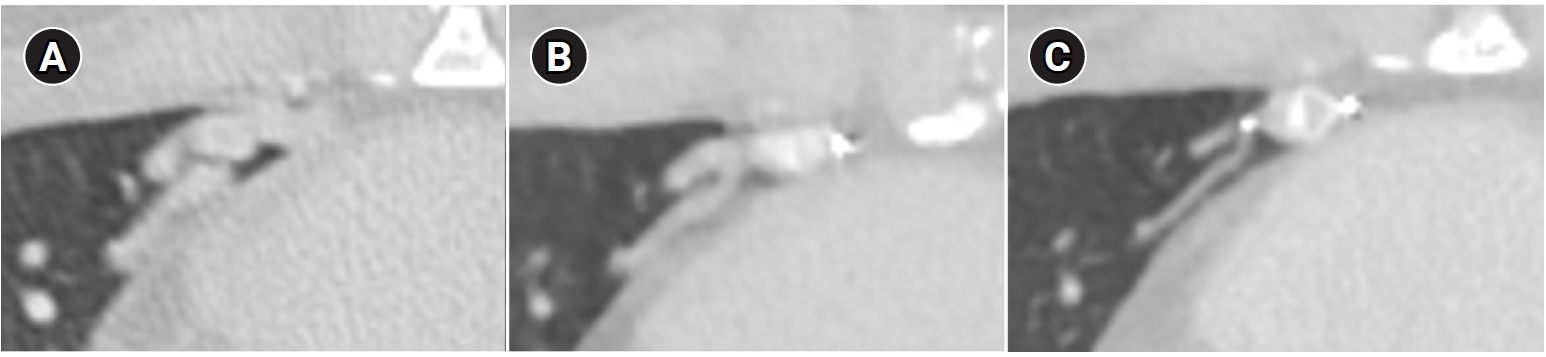

Fig. 9.Computed tomographic images of a patient with bilateral lower lobe pulmonary arteriovenous malformations treated with coil embolization. (A) Image without metal artifact reduction, showing prominent beam-hardening artifacts that obscure the evaluation of surrounding vessels and parenchyma. (B) Image with metal artifact reduction technique applied, significantly reducing beam-hardening artifacts and allowing for better evaluation of the adjacent vessels and parenchyma.

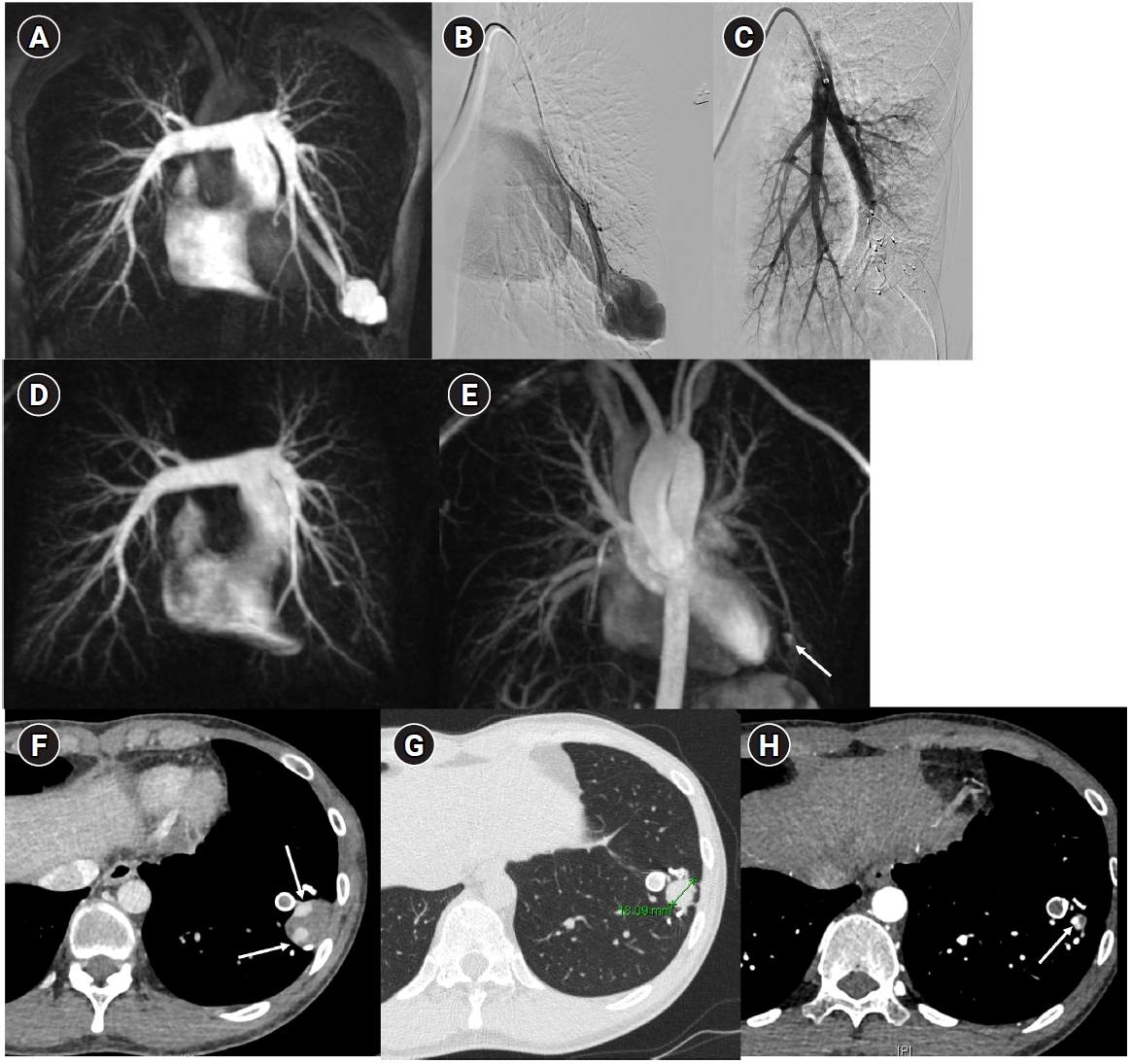

Fig. 10.Images before and after embolization using a vascular plugs in a patient with a large pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) in the left lower lobe. (A) In the time-resolved MR angiography, a PAVM in the left lower lobe exhibiting an early draining vein is observed. (B, C) The pulmonary arteriography also shows the same findings, and feeding artery embolization was performed using one Amplatzer vascular plug type II and six Amplatzer vascular plugs type IV devices. (D, E) In the 6-month follow-up time-resolved MR angiography, no rapidly appearing vein is observed in the arterial phase, and in the delayed phase, there is enhancement within the venous sac (arrow), which is considered part of the normal draining vein. (F–H) In the computed tomographic images taken at 1 month (F), 6 months (G), and 18 months (H) post-treatment, the thrombosed venous sac gradually diminishes, leaving only the normal draining vein (arrows) inside.

Table 1.Curaçao Criteria for clinical diagnosis of HHT

Table 1.

|

Criteria |

Description |

|

Epistaxis |

Spontaneous and recurrent |

|

Telangiectasias |

Multiple, at characteristic sites: lips, oral cavity, fingers, nose |

|

Visceral lesions |

Gastrointestinal telangiectasia, pulmonary, hepatic, cerebral or spinal arteriovenous malformations |

|

Family history |

A first degree relative with HHT according to these criteria |

References

- 1. Shovlin CL. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1217-1228; https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201407-1254CI.

- 2. White RI Jr, Lynch-Nyhan A, Terry P, Buescher PC, Farmlett EJ, Charnas L, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: techniques and long-term outcome of embolotherapy. Radiology. 1988;169:663-669; https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.169.3.3186989.

- 3. Ference BA, Shannon TM, White RI, Zawin M, Burdge CM. Life-threatening pulmonary hemorrhage with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Chest. 1994;106:1387-1390; https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.106.5.1387.

- 4. Cappa R, Du J, Carrera JF, Berthaud JV, Southerland AM. Ischemic stroke secondary to paradoxical embolism through a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation: case report and review of the literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:e125-e127; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.02.015.

- 5. Sanchez-Fernandez G, Garcia-Lopez F, Martinez-Bendayan I, Bello-Peon MJ, Marzoa-Rivas R. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation and embolic myocardial infarction in a patient with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:316-318; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccas.2019.11.046.

- 6. Fish A, Henderson K, Moushey A, Pollak J, Schlachter T. Incidence of spontaneous pulmonary AVM rupture in HHT patients. J Clin Med. 2021;10:4714; https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10204714.

- 7. Dakeishi M, Shioya T, Wada Y, Shindo T, Otaka K, Manabe M, et al. Genetic epidemiology of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia in a local community in the northern part of Japan. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:140-148; https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.10026.

- 8. Pierucci P, Lenato GM, Suppressa P, Lastella P, Triggiani V, Valerio R, et al. A long diagnostic delay in patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia: a questionnaire-based retrospective study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:33; https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-7-33.

- 9. Gossage JR. The role of echocardiography in screening for pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Chest. 2003;123:320-322; https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.123.2.320.

- 10. Faughnan ME, Mager JJ, Hetts SW, Palda VA, Lang-Robertson K, Buscarini E, et al. Second international guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:989-1001; https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1443.

- 11. Muller-Hulsbeck S, Marques L, Maleux G, Osuga K, Pelage JP, Wohlgemuth WA, et al. CIRSE standards of practice on diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43:353-361; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-019-02396-2.

- 12. Bari O, Cohen PR. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and pregnancy: potential adverse events and pregnancy outcomes. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:373-378; https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S131585.

- 13. de Gussem EM, Lausman AY, Beder AJ, Edwards CP, Blanker MH, Terbrugge KG, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy in women with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:514-520; https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000120.

- 14. Faughnan ME, Palda VA, Garcia-Tsao G, Geisthoff UW, McDonald J, Proctor DD, et al. International guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Med Genet. 2011;48:73-87; https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.2009.069013.

- 15. Mukhtar H, Iyer V, Demirel N, Bendel EC, Bjarnason H, Misra S. Embolotherapy for pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in the pediatric population with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias: a retrospective case series. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2025;36:823-832; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2025.01.047.

- 16. Hosman AE, de Gussem EM, Balemans WA, Gauthier A, Westermann CJ, Snijder RJ, et al. Screening children for pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: evaluation of 18 years of experience. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52:1206-1211; https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.23704.

- 17. Vargas-Acevedo C, Mejia E, Zablah JE, Morgan GJ. Fusion imaging for guidance of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation embolisation with minimal radiation and contrast exposure. Cardiol Young. 2024;34:1451-1455; https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951124000349.

- 18. Saluja S, Sitko I, Lee DW, Pollak J, White RI. Embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations with detachable balloons: long-term durability and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:883-889; https://doi.org/10.1016/s1051-0443(99)70132-6.

- 19. Ratnani R, Sutphin PD, Koshti V, Park H, Chamarthy M, Battaile J, et al. Retrospective comparison of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation embolization with the polytetrafluoroethylene-covered nitinol microvascular plug, AMPLATZER plug, and coils in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:1089-1097; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2019.02.025.

- 20. Tau N, Atar E, Mei-Zahav M, Bachar GN, Dagan T, Birk E, et al. Amplatzer vascular plugs versus coils for embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:1110-1114; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-016-1357-7.

- 21. Yu Q, Hofmann HL, Shetty S, Liao C, Navuluri R, Zangan S, et al. Transarterial embolization for pulmonary arteriovenous malformation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2025;36:1239-1253; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2025.03.011.

- 22. Kajiwara K, Urashima M, Yamagami T, Kakizawa H, Matsuura N, Matsuura A, et al. Venous sac embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation: safety and effectiveness at mid-term follow-up. Acta Radiol. 2014;55:1093-1098; https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113512123.

- 23. Hayashi S, Baba Y, Senokuchi T, Nakajo M. Efficacy of venous sac embolization for pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: comparison with feeding artery embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23:1566-1577; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.008.

- 24. Dinkel HP, Triller J. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: embolotherapy with superselective coaxial catheter placement and filling of venous sac with Guglielmi detachable coils. Radiology. 2002;223:709-714; https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2233010953.

- 25. Nagai K, Osuga K, Kashiwagi E, Kosai S, Hongyo H, Tanaka K, et al. Venous sac and feeding artery embolization versus feeding artery embolization alone for treating pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: draining vein size outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021;32:1002-1008; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2021.03.544.

- 26. Abdel Aal AK, Ibrahim RM, Moustafa AS, Hamed MF, Saddekni S. Persistence of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations after successful embolotherapy with Amplatzer vascular plug: long-term results. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2016;22:358-364; https://doi.org/10.5152/dir.2015.15262.

- 27. Lee SY, Lee J, Kim YH, Kang UR, Cha JG, Lee J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Amplatzer vascular plug type IV for embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:1082-1088; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2018.07.029.

- 28. Latif MA, Bailey CR, Motaghi M, Areda MA, Galiatsatos P, Mitchell SE, et al. Postembolization persistence of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: a retrospective comparison of coils and Amplatzer and micro vascular plugs using propensity score weighting. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2023;220:95-103; https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.21.27218.

- 29. Tucker WD, Arora Y, Mahajan K. Anatomy, blood vessels. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- 30. Meek ME, Meek JC, Beheshti MV. Management of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:24-31; https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1273937.

- 31. Hong J, Lee SY, Cha JG, Lee J, Kim D. Iatrogenic pulmonary artery perforation associated with 5-Fr catheter manipulation during pulmonary arteriovenous malformation embolization with a vascular plug. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:970-973; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radcr.2021.12.054.

- 32. Woodward CS, Pyeritz RE, Chittams JL, Trerotola SO. Treated pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: patterns of persistence and associated retreatment success. Radiology. 2013;269:919-926; https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13122153.

- 33. Expert Panel on Vascular Imaging, Pillai AK, Steigner ML, Aghayev A, Ahmad S, Ferencik M, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM): 2023 update. J Am Coll Radiol. 2024;21(6S):S268-S285; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2024.02.028.

- 34. Lee DW, White RI, Egglin TK, Pollak JS, Fayad PB, Wirth JA, et al. Embolotherapy of large pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:930-939; https://doi.org/10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00815-1.

- 35. Mager JJ, Overtoom TT, Blauw H, Lammers JW, Westermann CJ. Embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: long-term results in 112 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:451-456; https://doi.org/10.1097/01.rvi.0000126811.05229.b6.

- 36. Hong J, Lee SY, Cha JG, Lim JK, Park J, Lee J, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) embolization: prediction of angiographically-confirmed recanalization according to PAVM diameter changes on CT. CVIR Endovasc. 2021;4:16; https://doi.org/10.1186/s42155-021-00207-9.

- 37. Kawai T, Shimohira M, Kan H, Hashizume T, Ohta K, Kurosaka K, et al. Feasibility of time-resolved MR angiography for detecting recanalization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations treated with embolization with platinum coils. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1339-1347; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2014.06.003.

- 38. Choi J, Lee SY, Park KB, Park JK, Yang SS, Oh CH, et al. Usefulness of metal artifact reduction on CT angiography after massive coil embolization in peripheral AVM. Eur J Radiol. 2026;195:112606; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2025.112606.

- 39. Kawai T, Shimohira M, Ohta K, Hashizume T, Muto M, Suzuki K, et al. The role of time-resolved MRA for post-treatment assessment of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: a pictorial essay. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:965-972; https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-016-1325-2.

- 40. Goyen M, Ruehm SG, Jagenburg A, Barkhausen J, Kroger K, Debatin JF. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation: characterization with time-resolved ultrafast 3D MR angiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:458-460; https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.1066.

- 41. Hong J, Lee SY, Cha JG, Lim JK, Cha SI, Do YW. Large venous sac thrombus formation after endovascular embolization of ruptured pulmonary arteriovenous malformation: usefulness of time-resolved MR angiography in decision making. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:1892-1895; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2020.02.019.

- 42. Hong J, Lee SY, Lim JK, Lee J, Park J, Cha JG, et al. Feasibility of single-shot whole thoracic time-resolved MR angiography to evaluate patients with multiple pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Korean J Radiol. 2022;23:794-802; https://doi.org/10.3348/kjr.2022.0140.